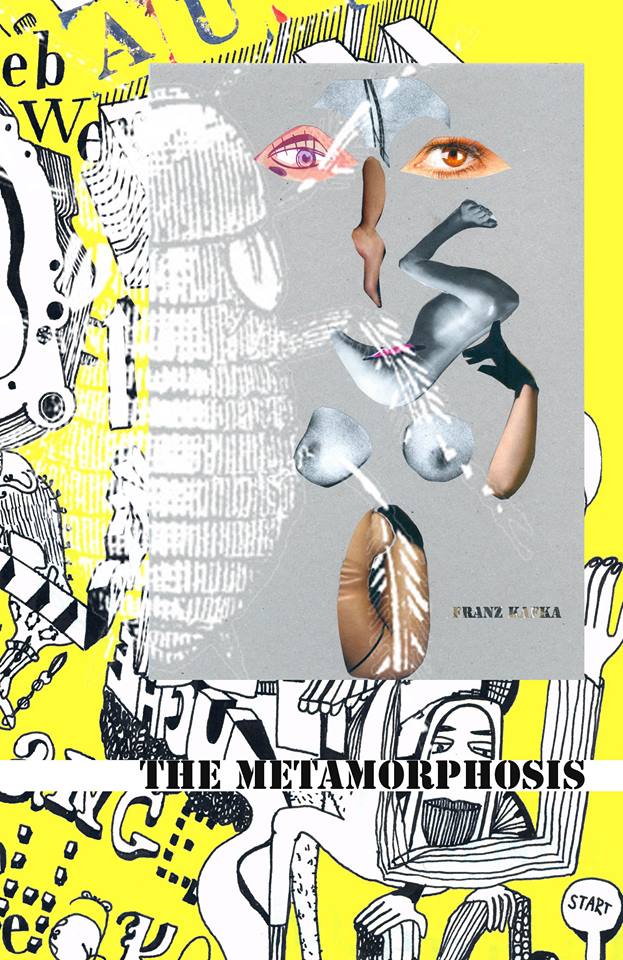

Am I turning into a surreal Kafka-esque monster? Or is this what teenage dysphoria feels like? Kafka’s story of a man’s sudden metamorphosis into a huge cockroach may seem a bizarre narrative for someone transgender to relate to, but the feeling of discontent many trans people have towards their bodies isn’t too far away from what the main character feels. This rewriting of the nightmarish tale rephrases the short story’s subject from a grotesque and unwilling transformation into a bug, to a transgender (and specifically non-binary) experience of puberty and transition. Without the insect wings and exoskeleton, the classic ‘Metamorphosis’ can exist as a trans narrative, means to us.

One morning, when Grega Samsa woke from troubled dreams, they found themselves transformed in their bed into a strange creature. They lay on their slim back, and if they lifted their head a little they could see their soft belly, slightly domed and rising rhythmically as they took in each breath. The bedding was slipping off Grega’s body, hardly able to cover the curves of breasts and hips as they squirmed in just-woken confusion. Grega’s unseen legs, pitifully thin and delicate, were stretched out and uncomfortable, in slight pain as if they had just finished growing.

“What’s happened to me?” they thought. It wasn’t a dream.

In the night their body had been moulded by some mysterious force like clay; unfamiliar and pliable lumps and irregularities on their body seemed to have been formed under the hands of a mirthful abstract artist. As they regarded the strange figure on the bed with wide eyes, Grega became increasingly aware that their previously nondescript form was suddenly transformed into one they found truly monstrous.

Sitting up they felt with elegant or spindly hands the gross and new contortions of their flesh. They untangled their limbs from the linen, unwittingly revealing soft smooth skin moulded to unknown hills and valleys. Shutting their eyes so they wouldn’t have to look at the body so newly womanish that it was an abstract sculpture to them, Grega got up to lock the door. They moved clumsily, knocking into the desk on their way back to hide among the bed sheets and feeling the dull pain in the hip that hadn’t been protruding roundly like that before. Their consciousness hadn’t expanded to fit inside the raw warped body yet, the limbs were the wrong shape, the shoulders too small and round, and they didn’t understand why the waist curved like that.

Throughout the day Grega wrapped themself more and more tightly in the bedding as their parents talked from outside and knocked on the door politely, and then imploringly, and then frantically as the day went on. By the time the sky outside was dark enough for their parents to quiet and subside to the double bed in the house’s largest bedroom, winding down like clockwork dolls, Grega was distressed, sweating and tangled in sheets. Grega clambered out of their nest and towards the window, catching their reflection in it before the sight of the street outside solidified behind the glass. They shrieked a little and instead of going to look at the view, curled into a corner of the room and folded their limbs up close to them, shivering gently in confusion. They mentally listed the creatures they’d rather be: rat, cricket, toad, vulture, goat- anything please. ‘Please God,’ they hum under their breath, ‘let me be anything but this girl-like thing I never asked to be’.

The next day Grega unlocked the door. They covered their body in the sheet and couldn’t explain what was wrong when their parents came in to anxiously tug at them, speculate, and leave a tray of food and tea. “Is our poor daughter ill?” They asked aloud. “Is she stricken with anxiety or poor nerves?” Grega shuddered at their parents’ words of concern, which gave them much more dysphoria than familial comfort.

A few days later, Grega was crouched by the window without the sheet, eyes closed and imagination far away trying to escape the strange wrongness of the body’s skin, muscles, and bones, when their parents walked in with a tray each of small plates of food. Seeing the gaze of their parents fall on their new and terrifying skin, Grega leapt back behind the curtain.

“What’s wrong? Why are you jumping like that?” they asked. “We thought you’d be injured in some way, hiding in your room like this.”

Timid and trembling behind the drapes, Grega questioned them in a feeble voice which was so high as to be grating.

“You don’t see what’s wrong with me?” The two parents shook their heads and starting rhythmically nagging Grega about the ridiculousness of staying locked away like this in causeless distress. Once the parents left, laden trays remaining on the desk, Grega returned to their self-directed angst and circular ponderings of bathing in the holy fire at the church to wash their current form away, hopefully revealing the right one that must be trapped underneath it.

Over the next few weeks and months Grega wouldn’t venture out of their house to church, or even out of their room. Wrapped in their sheets like a corpse in a shroud, they’d lie most of the days as if trying to bury the dysphoria under the weight of blankets and stillness. They closed the curtains and stayed away from the windows, not wanting any sight of themselves; they wouldn’t let anyone into the room when they weren’t hidden.

Slowly however, Grega Samsa began to change again.

At first Grega didn’t notice this more gradual transformation; they thought it was just their imagination extending every hazy fantasy of the past months along the axis of reality. Their calves, which were the first to change, they couldn’t be sure about as they weren’t in sight often, but once Grega’s arms started to alter it was quite clear. They were always morphing slightly, but at some point before dawn, either Grega’s perception was dreamlike or they changed much faster. At that time each day, Grega could swear their arms were oozing on their bones, shifting, shimmering and hardening, and becoming different.

Their chest and stomach started transforming after that; the soft lumps and arcs disappeared and a new torso formed before Grega’s awed eyes. The flesh seemed to bubble and the muscle to stretch and deform and grow and reform, bones moving and merging as if commanded by something powerful.

Every part of Grega seemed to be at battle with the other version of itself; they often wondered whether the hips they kept hidden under the shroud each day or the hips forming new from the flesh would win. The knees were the last of these wars, and, as with the rest of Grega, the old and horrific ones were a memory hidden by the new shapes.

They peeled the thin white wrap off of their body and peeled the malcontent and disgust from it at the same time. Emerging from the languorous filthy air of their room, Grega went downstairs, feeling free from the entrapments of that distorted form. The parents sat on the sofa sipping tea at the bottom of the stairs as Grega, almost like a newborn with their new and enthralling legs, face, happily curling toes and fingers, descended. The two of them turned simultaneously, the father spilling tea slightly and the mother maintaining only a little more composure as they looked up in horror at the results of the clandestine transformation from soft embarrassed shapes to easy geometric wholeness. The mother and father exclaimed in choir-like unison, “What on earth has happened to you?”

Grega’s victorious smile dropped and their expression tensed to mirror the shock clinging to the faces of their parents. Confused, they looked down at themself briefly, and finding under their gaze the form in which they belonged, they lifted their deeper, softer voice from among the cobwebs in their chest, and announced,

“I’ve become how I’m supposed to be.”

This text review is part of Textasy, Sensa Nostra’s new text reviews section. Want to contribute?