What happens when a man discovers he’s gay but the culture he is raised in doesn’t address sexuality, much less homosexuality? James Schwartz, an LGBT poet and writer who grew up in an Amish community in Michigan, gives Sensa Nostra an inside look at what it’s like to grow up gay in a world where gender roles are strict and marriage between a man and woman is seen as an imperative.

The story of my life is a reflection of the global struggle for LGBT equality, a struggle that includes all members of society, including the Amish and Mennonites. Coming out for all LGBT Amish means being ostracized and excommunicated. Families must permanently cut us out of their lives and have no contact with us or they will get shunned.

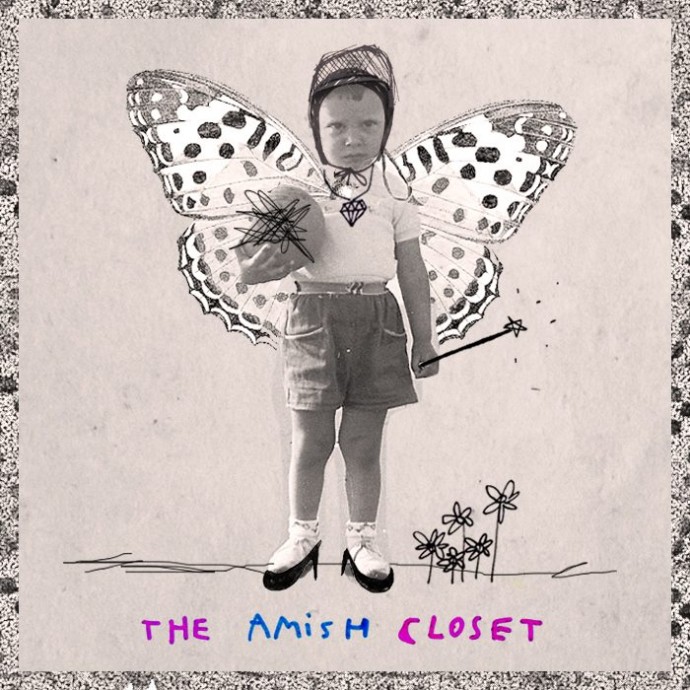

As Amish follow the church, not society, they haven’t progressed on gay issues—they see homosexuality as lust, and that is that. Amish same-sex marriage is prohibited even in a marriage equality state. If an Amish youth comes out as gay, he or she will be quoted Scriptures (Leviticus is a classic read), shamed and pressured to renounce his or her ‘sin’. The ‘Amish closet’ is a dark place of hopelessness and bondage.

Some Amish communities are stricter than others. The Swartzentruber Amish branch being the most conservative. Our church district in southwest Michigan’s ‘river country’ was less strict than many but not progressive by any measure. Kerosene lamps, no electricity, clothes washed in an old-fashioned hand washer, and the farmhouse heated by wood burning and oil stoves.

All Amish are pressured into being formally baptized into the church by their late teens. Roughly eighty-five to ninety percent of Amish choose to stay. Those who leave the church usually return, unable to bear the separation from their families. The ones who do leave for good usually join other conservative Christian churches.

When you’re baptized and join the Amish community you are making a promise for life to be an obedient church member and live within the group guidelines. Therefore, when a member breaks the rules the community shuns them until they repent and are voted back. This is the Amish way of maintaining the purity of the church, believing they are a chosen people. The world is viewed as a wicked and sinful place to be feared—best to keep as separate as possible from it.

Rumspringa, the Pennsylvania Dutch word for running around, is a period in which teenagers are allowed to party and go socializing before they join the church. The rumpsringa in our district meant barn/garage parties, beer, blaring Country Western music, and a little dancing. Some Amish don’t have a rumspringa, or it only consists of supervised youth socials and singings. No binge drinking, drugs, or clubbing.

My brothers and sisters are much older than me and left the Amish community, married and already had their own families when I was still young, so I always felt like an only child. I was an effeminate Mama’s boy, and from an early age I knew I was different, but I didn’t understand how or why. I went through a brief period of devout faith when I was young. I read the Bible and prayed, prayed, prayed: morning and evening devotions, prayer before and after meals, at church. When an ex-Amish relative came for a visit I pointedly informed her of her fate in hellfire because she wore makeup and jewelry. Mom said so.

This instigated a teary argument between them while I smugly watched on. It was a horrible thing to do, but I was self-righteously evangelical about it all and defiantly unrepentant. I was jealous of her clanking bracelets, fancy English clothes and frosted blue eye shadow. Of course I secretly wanted to wear jewelry and frosted eye shadow too.

A boy’s boy I was not.

I minced when I walked and gushed when I talked. I postured my hand on a cocked hip. My world was my mom. I would hang on her dress hem at all times and rush home to her from school, merrily chattering away as she prepared dinner. Around the house I was her constant shadow.

I disliked getting up early for the long buggy rides to church. On church Sundays I sat with Mom at church and wouldn’t hear of sitting with the other boys. Men sat with men, the boys with boys, women with women and girls with girls. When an Amish boy teased me about it, I would sass him after church with a hand on my hip, calling him a few names like dumb cow.

I gravitated emotionally towards women, happy in their company. Men were another matter. I was disinterested in sports and talk of crops, hunting and farming. From an early age I was aware of a certain animosity from some male classmates, Amish men in the community, and even family. The animosity puzzled me, as I didn’t understand that my effeminate mannerisms were a giveaway. I simply didn’t understand sexuality, let alone homosexuality. Sex within the Amish community is a taboo subject, and there was certainly no Internet, television, or film.

I once spent the night with an Amish classmate that turned into a one-night stand. Once we were in bed it just happened instinctively. Neither of us got any sleep, and over the breakfast table I realized neither did the rest of the household. I was never invited back and he barely spoke to me afterwards.

Not knowing any openly gay people (Amish or otherwise) deepened the mystery of this experience. I had no sexual desire for women and with sex being a taboo subject I had no reference point. It all sort of came together for me when I began reading books with gay characters. Michael Cunningham’s early novel Flesh and Blood (1995) comes to mind, which I read after this one-night tryst with my classmate. It was around this time that I realized I was gay.

As I grew older I knew if I stayed Amish I would have to also stay in the closet and be pressured to marry a woman. The idea of marrying and living a lie offended my soul. I didn’t want to father children. I knew I would never be happy living the Amish life, if I was honest with myself. I also felt there was another world out there and I could never see it as evil.

Once I accepted my sexuality I wanted full gay liberation. I simply needed to muster the courage to step out, once and for all. I left the Amish officially in my late teens when I stopped going to church and eventually came out. My mother passed away when I was nine, so from that point it was just Dad and me. Every other Sunday he would make me go with him to church services and this was how it happened. After the 5 to 10 mile buggy ride to church I hopped off when we arrived and walked home. This happened two or three times until Dad realized I was serious about not going to church.

Dad was my hero: good-natured, always quick with a joke and smile. I was scared to come out to him, as I didn’t know what he would say. Despite his Amish ignorance on the subject of homosexuality, Dad was a model of Swiss tolerance.

“Dad I’m gay.”

His reply?

“You had better join the church and get a wife.”

“D-a-a-a-d!”

I don’t know if he truly understood, but he wasn’t going to kick me out or treat me badly. The Amish approved of me staying at the farm but not of my open homosexuality. Dad was upset that I didn’t join church, but he loved me unconditionally. I wasn’t kicked out of the community entirely either, just snubbed by its members. Some Amish are not so lucky.

I came out to everyone I knew by my early twenties. I started going to gay discos around this time, met my local LGBT community (family) and performed in drag shows. I transformed into a honey-blonde diva favoring little black dresses and Judy Garland numbers. I left home for several years, moving to Sarasota, Florida with a friend. I wanted my freedom, but in late 2004 Dad asked me to stay with him, as he was getting up there in years and wanted someone around the house. I didn’t mind, as I loved Dad and I could still hit the clubs on weekends.

I felt pure freedom when I left, the freedom to be myself and not worry about others judging me as a fallen sinner. I learned early on to consider my LGBT community family. When I walked into my first gay disco I was shaking. I was so nervous, afraid of getting heckled by a drag queen. I was, of course, immediately heckled by a drag queen, but it was mutual love at first sight. Many nights were spent in the company of drag queens, male dancers and other assorted nightlife characters, and I was welcomed with glittery open arms.

Going back to the Amish farm gave me the space to write about my nights out with cabaret legends. I got used to going from strobe lights back to kerosene lamplight. There was some culture shock, but overall, leaving the Amish and coming out was liberation. I was free to be myself and follow my heart.

Dialogue on LGBT issues is vital, as most Amish have little resource or support if they leave. I wanted to write about the gay Amish experience, be provocative, political and an artist. Not a farmer. Although I see farming as an important profession, it’s not my style. I love the struggle to be a writer and artist and having something meaningful to say.

To all LGBT Amish: follow your dreams and remember you are not alone.

Pingback: Suggestion Saturday: May 24, 2014 | On The Other Hand()