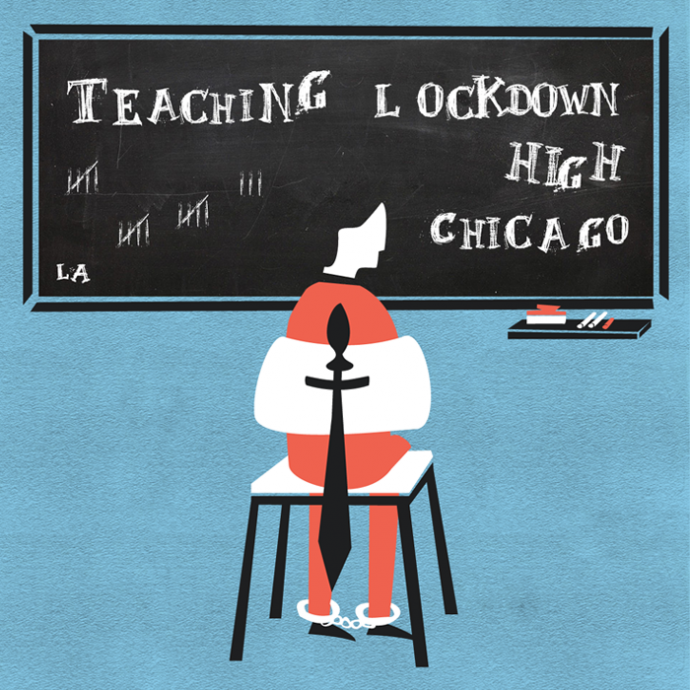

Cook County Jail is the largest detention center in the U.S., located in the heart of Chicago. It houses up to 13,000 men and women awaiting trial or transfer to other correctional facilities. Innocent until proven guilty, they spend from only a few days or months to up to five years locked up.

County jails are infamous for offering next to no activities to their detainees—the accused are simply to wait for the verdict. Luckily there’s one NGO set up to teach detainees career skills and give guidance to those sitting the standardized high school equivalency test. Their mission is to end correctional recidivism, making sure repeat offenders break the cycle of falling in and out of prisons. We talked to an ex-volunteer coordinator for this program. He shares his experiences, struggles and reflections on teaching to a captive audience.

Pretty much for the entirety of my adult life I was involved in social justice work. From the early age of sixteen I volunteered at an agency in my hometown that offered housing to ex-convicts, alcohol and drug addicts, and single mothers. I eventually moved to Chicago where a friend of mine told me about a job opportunity at Cook County Jail. It seemed like the perfect position, helping people get their lives back on track. I was trying to continue work that was important to me, and to be honest there was something sexy about it. Part of me was definitely turned on by the idea of doing something people—or at least the ones I associated with—would ever think of doing.

It wasn’t until I went to the jail for the interview that the seriousness of it all dawned on me. Going through the multiple checkpoints with metal detectors and security clearances was a bizarre experience. Afterwards I had to wait three months for the prison administration to a run security background check on me. In my mind I was developing an idealistic picture of what it would be like, but in the end it didn’t play out that way.

Originally I got a job as a volunteer coordinator at the school located inside the jail, more specifically inside the maximum security division for men. Many detainees don’t get their high school diplomas before incarceration. Some of them are simply dropouts; others repeatedly get into trouble with the law and so are unable to finish their education. Chicago public schools are a challenging environment anyway, even without these added factors. My job was to recruit volunteers from the outside who could provide educational activities to the guys locked up.

The exciting thing about the job—as it was presented to me—was providing the detainees with activities I deemed worthy. Jail is so freaking boring and if you’re not engaging yourself with something meaningful you’ll surely run into trouble. I was looking for people or organizations that the detainees could relate to. The guys who ran the bible study group, for example, were ex-gang members. They spoke from life experience. Surely they’d talk about how they’d found Jesus and stuff. But to me I didn’t give a damn whatever helped their lives get back on track.

Getting people excited about working in the jail wasn’t a problem. They could come up with all the best ideas and plans, offering the best services, but most of the time I just had to tell them to wait. All the applicants needed background and police checks, which equalled a mountain of bureaucracy. It was rare that I saw someone go through the entire process to eventually stand in front of a class.

I ended up teaching math myself, which I hate, but luckily it was only at a high school level. I quickly started realizing that I would get none of the support I was initially promised. I don’t know if it was even legal or compliant within the rules, but the bulk of the programs I ran by myself in front of eighty detainees charged with violent offenses, with only one corrections officer (CO) present.

I had to grow eyes in the back of my head. After each class I would count the pencils, and when there’d be one shy and I’d say, “Look, I am going to turn around and this pencil better magically appear or I can tell the COs and all of you are going to get your assholes checked—and I know you don’t want that.” Even the chairs were a problem. They were made from metal and some of the bars would slowly begin to bend. Detainees that came in every day picked the same chair and slowly work at it and until it eventually broke off and could be to made into a weapon. They did this to either protect themselves or kill someone. It weighed heavily on me knowing that my negligence could make me a accessory to a murder.

One time a colleague of mine wasn’t so diligent. In some down time he was playing Scrabble with his students and I happened to be there that day. “Did you account for all your materials?” I asked him. I looked and there was one letter tray missing. A few days later I saw a CO walking down the hall with an evidence bag containing the scrabble tray sharpened into a shank. It sounds crazy, but that was just everyday life.

I made it a policy to never ask questions or concern myself with the charges brought upon my students. I didn’t want to know, judge or question the ethics of helping them. On certain occasions I did find out. I remember a guy asking me to photocopy a document he needed for his court case the next day. As I was walking towards the copier, I read it. He was accused of kidnapping, beating and raping a fourteen-year-old girl. I looked in his face as I handed it back to him thinking, “Did this guy do this? Did he not? Should I be treating him the same as anyone else? Or is this person just piece of shit and that should he go to prison or even die for what he’s done?”

I never knew what I was walking into each morning, what had happened the night before, or who would still be there. It happened once that a detainee I was personally working with got stabbed and killed—the atmosphere was completely unpredictable and chaotic. I tried not to get upset by the things I read, or saw, or what people would say. It was an environment full of alpha males, and they’d talk to each other in such homophobic, sexist and misogynistic ways that I found it truly repulsive. When you work in such a stressful and hostile environment you realize you have to shut down emotionally. And that affects every aspect of your life. You can’t go to work and flip off all your emotions and then flip them back on when you get home. Essentially, I became a zombie, a hollow person. I don’t think I was cut out for that work. At least I’m not doing it now.

My colleagues in the organization where either Christians who perceived every tragedy as one of god’s plans, or they were just in it for the money and didn’t care about what was going on around them. Above that, the director of the NGO had all kinds of dirt on him. We had a closet full of schools supplies, TVs, DVD players and laptops that weren’t being used. He needed to keep the budget inflated so he could make this program seem like it was doing something worthwhile. Not only that—he was a sleazy dude who had sex with the female employees and consequently didn’t dare fire them.

There’s a saying that NGOs exist, but their goal is to not exist, meaning that they will work until the problems are gone. Unfortunately, when they get large enough, they only seek their own preservation. This was certainly the case for the organization I worked with. It saddens me that the American government doesn’t take responsibility for dealing with correctional recidivism, leaving it up to sham programs like this. Finding out that there was no cooperation or support destroyed my motivation and ambition. I became a textbook NGO burnout.

My imprisonment in Cook County Jail was self-imposed, and the difference between the detainees and me was that I had a way out. That place brings out the absolute worst in people. I would go so far as to say that everybody involved deserves some sympathy, and if nothing else some recognition and understanding. Corrections officers and police have a reputation of being shitty, abusive, power-tripping dickheads. But I think its interesting to note that in the US people in these kind of high-stress positions are more inclined than in other countries to resort to alcohol, substance abuse, domestic violence and suicide. Clearly there’s something completely wrong with our criminal justice system. The same goes for the detainees who constantly need to look out for their own safety. In the U.S., jails are all about punishment and power and not about reconciliation or rehabilitation. An ex-convict will live with his stigma for the rest of his life.

In the beginning, when I recruited people for the program, I used to say, “How would you feel about these guys coming back into your community? Wouldn’t you prefer that they had some sort of skill or vision to make their lives better, prevent them from falling into a downwards spiral?” But after a while I couldn’t stand behind that ineffective organization anymore. It was just a bandage on cancer.