Common belief suggests that homosexual men in the armed forces and police force face a higher amount of discrimination than elsewhere. Media coverage on gay issues contributes to the image of the forces being close-knit environments, where masculinity and machismo have an almost iconic significance, inevitably sympathetic to homophobia. Can we however still view this as an accurate representation? Police Officer Alan, and head of the GPA (Gay Police Association) in Scotland, talks about his reality of being gay in the Police Force and how things have changed for the better.

I’ve been a police officer for 18 years and came out 16 years ago. Back then we are talking about a time when the police service was transitioning. It was just after the Steven Lawrence case (highest profile racial killing in the UK in the 1990s), and the ensuing inquires which conclusively deemed the force to have institutional issues concerning racism. Ultimately, if there is racism within an institution, you can be pretty sure you’ll have homophobia, sexism, and other issues like that as well. It took a while for the police force to accept that its institutional nature was proving inflexible and slow to adapt to the changes that were taking place in society. The perception, then, was that the police were being racist as well as homophobic and targeting gay men and raiding gay bars. These incidents happened before I joined the force, but there was still the culture within the police that being openly gay within the police wasn’t really a thing to do. Nobody in the police here was openly gay – it was an unwritten rule to hide the fact. People felt comfortable being homophobic. What’s often termed as ‘canteen-culture’ refers to the fact that people talk about things in a way they feel they can get away with, using language that is racist, sexist, or homophobic. You wouldn’t talk about ‘gay people’ you’d talk about ‘those poofs’. So the language didn’t help this internal culture and if you heard people using that type of language you’d certainly be less inclined to come-out. It wasn’t really until the early 2000’s that this attitude in the police started to be challenged and ‘diversity’ became part of police training. However when it first started it centred around racism, it didn’t really tackle any other aspect of diversity. So when I joined, it still had a long way to go.

It took me two to three years to come out … I think because the culture just didn’t allow it. Having said that – it’s very difficult to be in the closet. You have to lead a double life, because being in the police, it’s like a family, everyone wants to know your business, you feel as if everyone is talking about what they do so you have to make things up and lie about what you were doing at the weekend and who you were out with. It becomes complicated. This can result in higher stress-levels, coming to your work and having to constantly think about covering your back. So for me that’s what was becoming increasingly difficult. I wasn’t prepared at that time to come-out, because I was quite scared and I wasn’t prepared to just announce it to everyone, but I started tentatively speaking to a few people that I felt I could trust with that information. Even that was difficult because you don’t want people to react negatively, if you’ve never come-out before you don’t know what to expect. Fortunately the first few people I did speak to in confidence, were very supportive. Later on however I was forced to come out because I was being asked questions about an incident and it meant that I couldn’t avoid talking about where I’d been unless I lied about it, and it would have caused trouble in terms of the job. So I just had to basically admit during an interview that I was gay.

Whilst I didn’t mind because it took a weight off my shoulders, it was quite stressful. I think at that time most senior officers just didn’t know how to handle it, it was a bit like: ‘take a few days off to let the dust settle’. Bear in mind, sixteen years ago the fact that you are openly gay and in the police meant that the newspaper ‘The Sun’ actually got in touch to run a story about the fact. For them it was headline news! When I got back from my few days off (and I was actually really pleased about that because the weather had been nice), I came in through the back door because I was a wee bit concerned about what people would say so I thought I’d maybe try and sneak in, but then one of the training sergeants came over and shook my hand and just said ‘well done!’, and ‘you’ve got my support ’. I’d had no idea people would generally be like that.

There were a few people on the shift that I worked with who felt uncomfortable I think. Maybe they felt awkward about saying anything and maybe worried about saying the wrong thing. These were people I’d worked with for two or three years, we all knew each other really well and I think they potentially just felt a lack of confidence in themselves, whereas I wasn’t worried about them saying anything wrong unless it was done in the wrong way. I think also some were quite annoyed at the fact that I hadn’t told them or how they perceived me as having lied to or not trusted them, so some people maybe just didn’t understand what it’s like to be gay and why you might end up hiding in the closet as the term goes. So it was tricky but overall it was a relatively positive experience and that was at a time when I thought it was the last thing in the world I’d want to do, I mean I thought that being openly gay I wouldn’t have been able to get into the police never mind survive it. So it was an opportunity for me then, and afterwards I realized that homophobia was fuelled a lot more by perception than reality – and I’m not saying that my experience is what happens to everybody, we all have different experiences, but for me it changed my outlook. The homophobia was in my head, because you build up these demons over years and years when you’re not openly gay, and you consider the world to be against you and everyone to be homophobic.

That isn’t to say I haven’t experienced homophobia in the police force, of course I have, but possibly no more than I would have experienced anywhere else. In fact it was always compensated by the amount of people for whom it wasn’t an issue and who were very supportive, so the experience of coming-out in the police force was generally positive.

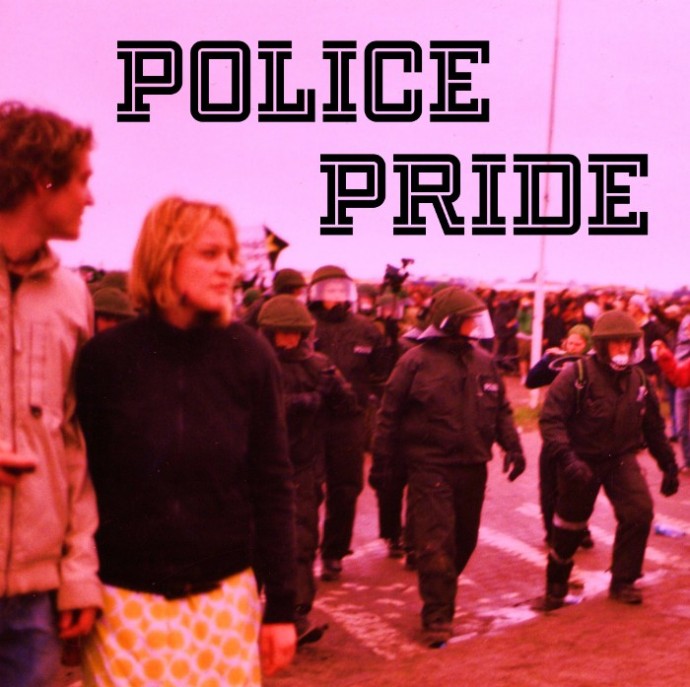

However when I came out I didn’t know anyone else within the police who were out and I felt very isolated. When I found the GPA, it was about finding others who were in the same boat as I was. People were fine with the fact that I was gay, but often reluctant to talk about it i.e. ‘We don’t need to know about you and your boyfriend’ – although they felt fine talking about their girlfriends with you. So the environment wasn’t one I felt to be equal from that point of view, and that gets you down and makes you a bit depressed. What the GPA did for me was to put me in touch with people who I could talk to about the same things and have that level of understanding. The big event for me was a summer social in Brighton. I drove all the way from Glasgow and it was brilliant: they had hired a hotel and there was things going on all weekend, it was like a big party and you could relax and chill out and meet people and make friends. We all had an affinity and it was great to be there. I had a wonderful time and I realized this organization means something to me and it’s made a difference in my life. So that’s what incentivised me to start it up here in Scotland so I could share my experience with others. One of the most positive events in my life was in 2004, when a colleague and I were allowed to take part in the London PRIDE parade in our police uniforms. It was the first time two Scottish police officers, had not only been allowed to wear their uniforms in the Pride event but it was also the first time two Scottish police officers had been in it, marching amongst so many others from everywhere – it was a wonderful experience. Back then the police taking part in gay pride was still a big issue and big news. The press were there, desperate to try and get us to hold hands and kiss just so they could get a controversial article out of it. We had however been briefed to act professional and walk in line and not give the media the titillation they were looking for.

The experience of wearing my uniform in my first PRIDE event in London, with all the people and claps and cheers, it was just wonderful and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t shed a tear. Since then I’ve always encouraged people to take part because you get a sense of pride in what you are doing and that’s the whole point. Those two events were very uplifting. Hundreds of Police officers from all over the country came to take part and I didn’t feel isolated anymore. Those are things that the GPA did for me. Now the Scottish GPA (also a member of the European GPA) organises many events nationwide. We work toward equal rights for LGBT police service employees, and we offer support and advice. Recently we had a gay police couple come-out to their families, who sadly rejected and kicked them out of their homes. We were there for them to guide them through such a rough patch. People trust us because we are an independent organisation too, so they know there’s no one pulling any strings above us and we are able to tackle any issues that might arise within the force independently. The police is far from perfect, we still have a lot of work before us, but we have come a long way.