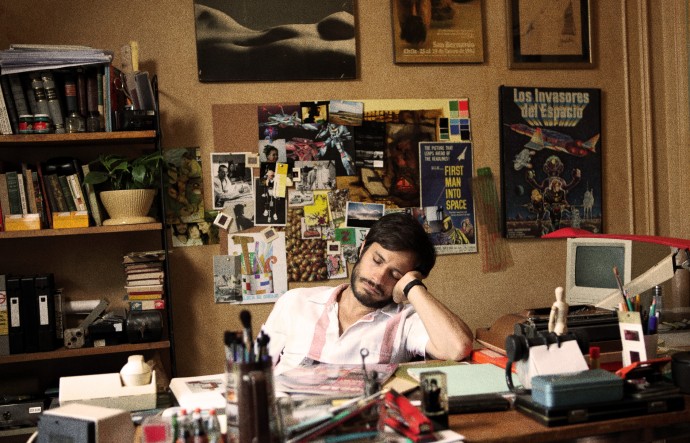

NO is a Chilean film, directed by Pablo Larraín and co-starring Gael García Bernal. This film relates the events that lead to the ending of Pinochet’s dictatorship. To make it short, it tells how an advertising campaign blew away the dictature. We are in 1988. The main character is René Saavedra, a well-succeeding advertising agent. He drives a sports car, is very proud of the microwave he just bought, and does not care much about politics. In fact, Pinochet’s ultra-capitalist policy is a good thing for his business. When put under international pressure, Pinochet is forced to organize a plebiscite : what is at stake is the survival of his regime. If Pinochet wins, his mandate will be prolonged for eight years. If not, elections will be organised. While everybody thinks this referendum will be framed by the regime, Saavedra accepts nonetheless to lead the advertising campaign for the “NO” to the old dictator. Saavedra elaborates a plan to make this campaign successful : he will sell Happiness and Joy.

With such a topic, we could have expected the filmmaker to show the misdemeanours of this infamous dictator, giving to his film a dark and thrilling atmosphere. In the same way, we could expect a harsh documentary approach that generally fits the will to make a political lampoon. Yet, Chilean director Pablo Larraín opts for a much lighter approach to the subject and wipes away all of our expectations. Though some of its scenes are quite tense, No does not tend to be a heavy movie, as it focuses almost exclusively on the advertising campaign that preceded the referendum. By doing so, it is as if Larrain were following the same path that Saavedra selected : making a seducing object rather than a traumatizing slagging off. In addition, Larrain also softens the seriousness of this problem as he does not elect the documentary approach I was mentioning but voluntarily blurs the limits between fiction and reality.

In order to recreate the aesthetical aspect of television at that time, Pablo Larraín opted to shoot with a 1983 camera, which results in a square frame and a very visible film grain. Though the result is quite ugly, its value comes from the efficiency with which it deeps us into these years. This method allows Larraín to mix his own images with archive footage from 1988 relating the events as they unfolded. Though this story is History it is definitely told in present tense.

“History” : the big H… word. Larraín took some liberties concerning it. First, as he focuses only on the advertising campaign and sticks with his main character’s point of view, the movie almost tells that the advertiser alone won the war against the dictator. Consequently, this movie eludes almost completely the street campaign lead to talk people into registering on the electoral roll. It also eludes how the Generals and the Western powers that lead Pinochet to power finally discreetly dropped him, with the noteworthy exception of Margaret Thatcher.

In fact, this movie tends to be much more than a mere praise to the democratic effort that put Pinochet out of power, it is not that kind of patronizing historical pompous fresque. With a more critical, though not too heavy-handed point of view, Larraín shows a time when political activism turned into marketism. Indeed, when Saavedra joins the “No” side, he is shown the TV spots that have already been made by other campaign advisers. These spots focus only on the sufferings caused by the dictature, denouncing the rapts and killings ordered by the regime. Though these spots relate the ugly truth about Pinochet, Saavedra offers a different approach. In order not to be censored and also to give confidence in the Chilean people in this election, he argues that this campaign should focus on the concept of Joy, their slogan being “Chile, Joy is coming”.

Though the movie ends after the removal of Pinochet from power, it is a portrayal of the Chilean society that appeared after the democratic transition. Saavedra is the incarnation of this outcoming society. He is a child of both Pinochet and his socialist predecessor Salvador Allende. His father was an opponent to Pinochet’s coup, and yet Saavedra abundantly enjoys the ultra capitalistic regime established by Pinochet as I stated in the introduction. In spite of his father’s past, Saavedra does not care about politics, though he craves for a little more freedom of speech.

Consequently he leads the campaign for the No with the tools he knows. When presenting his own first TV spot for the campaign, Saavedra is accused of sabotage by some of Pinochet’s historical opponents. This spot does not refer to Pinochet as a dictator and voluntarily ignores the sufferings of the left-wing opponents. Whereas his clients expect him to make campaign for “Democracy”, Saavedra realizes that, by organizing this referendum, “the old man has taken hold of the word Democracy” therefore they have to find a solution, or better said “a product that is sufficiently appealing to old ladies and to old people”, hence the choice to make this campaign focus on Joy. His main client José Tomás argues that “democracy isn’t a product”. The final victory of the No side tends to show that democracy is more easily sold this way than by reasserting the misdeeds of the dictature.

This initial decision creates some turmoil on the No side. Infuriated by this absence of memory towards the victims, one the political leaders of the Coalition walks away from this campaign, considering that it is only a way to legitimize the coming victory of the Yes side, and stating that he wants a change, but a real change, not at all cost and invokes the “ethical limits” linked to politics that do not apply to advertising and considers that Saavedra may have “lost perspective on his editing table”. The most interesting part is the link established by this political leader between the shape of the campaign and the shape of the probable victory. How the campaign is lead influences what the final victory will lead to.

“It looks like a Coca-Cola ad.” One other activist defines in these words the first draft of the advertising campaign proposed by Saavedra. Indeed this first draft is a mere editing of footage taken from commercials in order to evoke Joy. The origins of these footage are quite obvious when you look closely at this first draft. When talking about the Chilean society that originated from this victory, Larraín describes it as a “gigantic mall”.

When Pinochet made his coup with the help of the CIA, the aim was to overthrow Allende’s socialist regime and to establish an ultra-capitalistic regime that later on inspired Reagan and Thatcher’s policies. Clearly, the victory of the No side did not cause a U-turn in the economic and social policies of the country. Such socialist reforms as those undertaken by Allende were never conducted again. It just brought a succession of not too bald liberal presidents, which has been put to an end in 2010 with the election of the conservatory Sebastián Piñera.

In addition, Pinochet was never convicted eventually. He remained as Commander-in-Chief in the Army until 1998 and then began a life-term mandate as senator. This movie No, though a joyful and colourful movie ends with a bitter note. It ends with a loop, the final scene echoing the very first scene. The good and the bad guys are all present in the upcoming Chilean society, and “they all lived happily ever after”… Advertising eventually replaced politics. What about Justice ? What about Truth ? These are not comforting words. What about “social reform” ? That’s a scary word. Where the fuck are “politics” in the debate nowadays ? That word can’t be sold. What kind of victory is that ? This is the main question asked by No.

Saavedra keeps introducing his draft to his clients with these words : “Today, Chile thinks about its future”. Larraín and other Chilean filmmakers keep wondering about its past.