Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is the classic children’s tale of a boy who is plucked from poverty and thrust into a magical world of everlasting gobstoppers, fizzy lifting drinks, and three-course-meal-flavoured bubble gum.

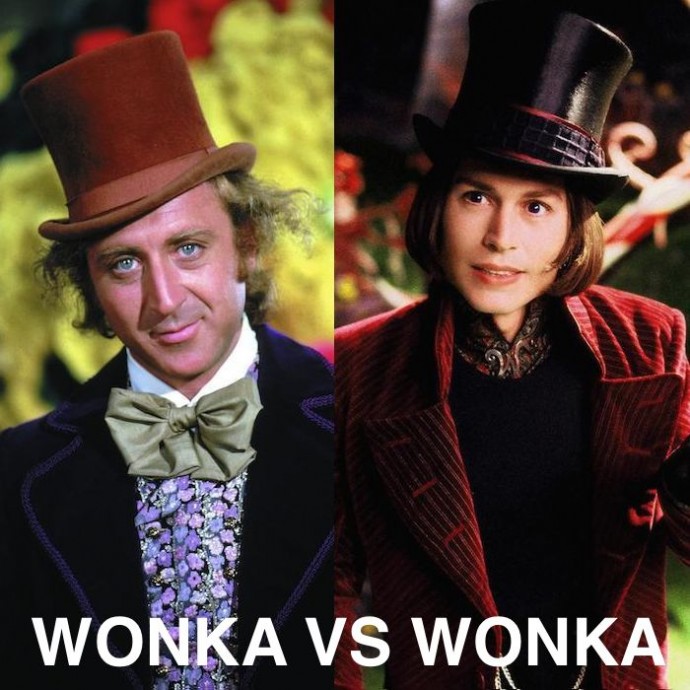

It has been adapted for cinema twice. The first film, made in 1971, stars Gene Wilder as the eponymous factory owner; the second is a 2005 reimagination at the hands of director Tim Burton. This time it is Johnny Depp who dons the top hat and purple velvet and commands the legion of Oompa Loompas.

Though both actors portray the same role: the showman, the reclusive genius, the chocolatier extraordinaire, the characters they play, and as a result the films in which they star, could not be more different.

The difference between the two characters is epitomised by their respective on-screen entrances.

As Wilder steps out of the Wonka factory, the watching crowd is silenced by the sight of their secretive hero: a seemingly frail old man who hobbles towards them with the aid of a cane. The cane slips out of his grasp and Wonka begins to teeter, unsupported, precariously leaning at an unsustainable angle before diving at the last moment, into an acrobatic roll that brings him to his feet with a broad smile on his face and a twinkle in his eye.

Here is our first Willy Wonka: master of the unexpected, impossible to read, a man of eloquence and panache who speaks in riddles and poetic asides. He is

capable of incredible warmth and kindness. Yet, he is also a borderline sociopath who curses the misfortune of having his chocolate river contaminated by the greedy child who is drowning in it and utters an uninterested, “Stop. Don’t. Come back.” as the various other obnoxious brats exploring his factory run off to meet their just deserts.

Compare with the second film. As the guests await Depp’s Wonka in the snow outside his factory, their elusive host is absent.

The grand entrance they are treated to is a gaudy theatre of animatronic marionettes that is set ablaze by poorly managed pyrotechnics and, with the melting plastic faces of the puppets and eyeballs rolling out of sockets, quickly begins to border on the nightmarish.

Who should let out a juvenile titter and applaud the grotesque spectacle with latex gloved hands but Mr. Wonka himself who has joined his guests, unnoticed.

There is a coldness and an unease from the moment Depp awkwardly introduces himself to the dumbstruck guests that from the very beginning leaves the audience in no doubt that this is not the same whimsical rogue that greeted Charlie and his counterparts back in 1971.

Who then is this reimagined genius? This man who has lived in isolation for so long that he behaves like an autistic child? The answer is simple: Michael Jackson. Most obvious is the striking physical resemblance: the synthetically pale skin contrasting with black hair, the soft, prepubescent speaking voice, and childish idiosyncrasies. He is a saccharine genius of sorts who with his factory has built a Neverland, a shrine to a childhood desperately yearned for, a childhood lost at the hands of an authoritarian dentist father who strictly forbid the consumption of confectionary. The father in this case may be a simple construct of Hollywood producers, who seemingly insist that the importance of family must be included as a key theme in any child-friendly film, but it reflects perfectly the stolen childhood that Jackson likewise yearned for so fiercely.

Despite possessing the emotional maturity of the young child he so wishes to be, Depp’s Wonka is still a showman and his work still spectacular, in the same way that Jackson behaved with a perpetual razzmatazz that began to blur into the unravelling of a deeply troubled mind in his later years.

If Depp’s Wonka is the king of pop then Wilder’s Wonka is by comparison one of the great poets or artists.

His surrealism and rampant creativity are reminiscent of the great Salvador Dali who used to walk around Paris accompanied by his pet anteater on a leash. Comparison with Dali is perhaps not completely fitting, however, as so much of Dali’s work revolved around strictly adult themes or eroticism and death and a borderline obsession with the naked female form.

Wonka is an artist who values the beauty of childhood above all. Not in the way that Michael Jackson was alleged to, but in the way encapsulated by Pablo Picasso who is famously quoted as saying, “it took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

Further exploration into Picasso’s quotes on childhood provides other equally apt sentiments:

“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.”

“Everything you can imagine is real.”

This explains the self-enforced reclusion of Wilder’s Wonka inside his factory; he is a man of such genius that in comparison to the paradise of confectionary he has created – his world of Pure Imagination- everything else seems lifeless and drab.

And that this is why Wonka goes to the trouble of hiding golden tickets in chocolate bars and eliminating the shortlist of selfish brats around his factory to find an heir to his empire. Because above all he values the child-like ability to be truly creative without the mental burdens that adult life brings.

Rather than the futile pursuit of the innocence of a childhood lost, the twinkle in Wilder’s eye espouses the indefatigable pursuit of excitement, imagination, and adventure that so freely inspires children but ebbs away as hormones begin to rage and the drone of adulthood approaches.

There is a subtlety and intelligence that is vastly lacking in both Depp’s performance and the latter film in general. It is the same subtlety present in the earliest Batman TV series starring Adam West. This, like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, primarily meant to entertain children, but the action, the unfeasible plot twists, the animated BANGGGs and POWWWs of the fight scenes were composed with such style and self-awareness that it provided a constant atmosphere of dead-pan humour for intelligent adults to enjoy.

This same humour is present in every line that the masterful Wilder delivers but is reduced by Depp to little more than girlish sniggering and puerile puns, culminating in derivative slap-stick as Depp walks into the unseen wall of the glass elevator. To imagine Wilder’s Wonka entering the glass elevator (the device representing the pinnacle of his unhinged creative genius) in any other way than with an elegant pirouette of purple velvet and a whimsical remark is all but impossible.

Perhaps it is too easy to claim that this is a result of the “dumbing-down” of entertainment.

What may be more accurate is that it is a symptom of a film industry so driven by business that even the slightest deviation from the accepted tropes must be run past marketing departments and test audiences. If so, then Tim Burton and Johnny Depp must too be applauded for straying into the murky wilderness by portraying a character other than the All-American hero or a woodenly evil super villain.

Nevertheless, this reimagined Wonka lacks any of the warmth, humour, and for want of a better word, character of the original. Michael Jackson and Pablo Picasso were both geniuses in their own right, both capable of entertaining, amazing and dumbfounding in their own ways, but I know which I’d rather have dinner with.