When the wickedness gets to us, we have two choices: condemn it or embrace it. But the option of choosing doesn’t always lie in our hands. Sometimes we aren’t who we think we are. Remember that. Sometimes all logic, rationality, and sensibility fail in moments of uncontrolled chaos. Sensa Nostra dug into the darkness to lure out a monster, who—in the visual shape of a young innocent boy—had a horrifying personal story to tell.

Growing up with two older sisters, I never needed to compete with them, never needed to assert myself. At home I was always considered the young, sweet, little brother, and my feelings were always taken into consideration by the two of them. Judging by some friends’ experiences, this might not have been the case if I had grown up with two older brothers.

As a kid, my relationship with violence did not exist. I’ve always been quite shy. I’ve never needed to stand up for myself. I’ve never had to fight for my rights. I like to think logic wins arguments; no need to bloody your knuckles. I was like this even as a child: calm and analytical, never fighting over stolen toys or claiming the swings as my personal property. To summarise, I was civilized at a young age.

So I remember the shock when I first visited my friend Tom’s house. He and his older brother battled with each other: name-calling, competing, fighting. They’d wrestle, and I’d always feel rather misplaced.

As kids, Tom and I were tree huggers. We loved nature and spent most days playing in this big forest behind his house. When the city decided to cut down the forest to build new houses, we took down all of the warning signs saying that this was no longer public property and tucked them away. This revolutionary act thrilled my eleven-year-old personality. The incognito operation… You could feel like you were some sort of rebel. Obviously we couldn’t fight the system for long, and eventually the forest was bulldozed.

Soon after the destruction, Tom and I went to explore the lost land that we’d been fighting for. On a rare occurrence, Tom’s brother Jack joined us. Jack was thirteen, two years older than Tom and I. The woods had been totally destroyed, and dead tree limbs were scattered everywhere. The place looked like an environmental war-zone—instead of human bodies there were dead wooden figures. So like any kids, we played with the fallen limbs, swooshing and smashing the branches into the dead trees, mesmerized by the sounds.

Then, suddenly, they were off. Smacking each other with the limbs, the brothers battled and goaded me into the war. First they struck me on my calves, which I embarrassingly tried to joke away. Then they hit my back. Afraid of becoming an easy punching bag, I sympathized with my friend and struck back at Jack.

It became us against him.

The whipping attacks started playful, and then we heightened the force. It escalated into a hunting game—it felt as if we were in one of those horrifying, late-night movies that we would watch when our parents slept. And since we outnumbered Jack, we had the upper hand. We became the hunters, and I embraced the power of control.

Fuelled by adrenaline, the blows escalated to dangerous levels, and as my strikes hit harder, I felt nothing except the rush from the next swing.

Finally, Jack fell. The older one had fallen. We had won. But our savagery knew no limit. We continued beating him ferociously with our branches. For the eye it was perfect: the controlling feeling of having the vanquished beneath you. Our sense of hearing was practically gone. I could only hear the pounding of my heartbeat, and it pounded louder and louder.

What the hell are you doing, stop it! a voice echoed in my head. Was it my conscience finally saying that this was too much, that we had reached the limit and had gone far beyond that? No, it was a neighbour who had seen what we’d been doing—senselessly beating this kid, murdering a brother—and maybe he realized that we were incapable of ending it ourselves.

Abruptly we woke up from this trance, saw the blood, the motionless body on the ground, and then fled in panic. We returned to our old hideout, the woods. Slowly the adrenaline sank, and I came back to reality: the cruel reality that I had almost killed someone, a brother.

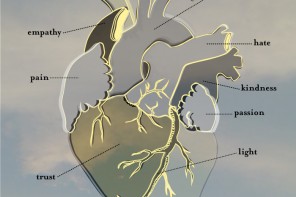

The tears were unstoppable. I felt guilty and ashamed, but also terrified. What happened to the civilized me? What happened to the civilized me who used logic instead of violence? Is this all it takes for me to go beyond my own boundaries? Tom asked me if I was alright. I nodded and went home.

Thinking about this today still startles me. This experience still has a huge effect on me. It kind of haunts me. What does this say about humanity, and about me in particular? I still haven’t come up with a proper answer to that.

Before this happened I was always certain that I could never hurt a fly, that I’m more civilized than that, that I’m not some animal acting on instincts. Today, twelve years older and a bit wiser, I look at it differently. I’m not as quick to judge people who go beyond their own limit, because I know that it doesn’t automatically make them into bad people.

When I was younger I used to love reading William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, a novel that follows a group of young boys who get stranded on an island, leading to their development of a dangerous social hierarchy. I always admired the boy Ralph, who wanted to stay civilized on the island and act “how grown ups would.” I used to think that I would act exactly the same if I were in the same scenario. When I look back today, though, if you had put me on that island, I’m not too sure anymore what I would do.