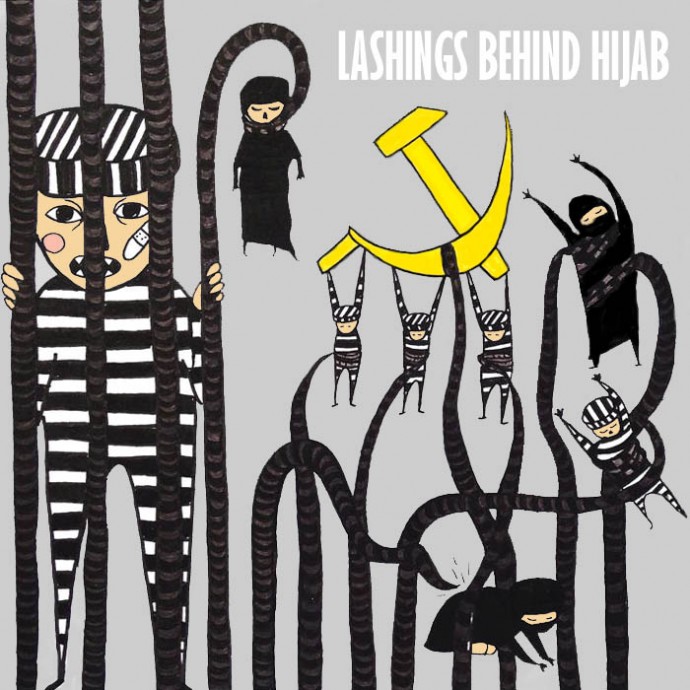

The hair that had been swinging in the massive revolution of Iran was now forced under a veil. She was a young woman with dreams and hopes. Together with other Marxist students, she formed an opposition against the reigning monarchy, and side by side they fought together with the Islamists. But when the Islamists came to power they betrayed their revolution friends and squeezed them into the horrific cells of Evin Prison in Tehran. Monireh, who now lives in exile in Germany, tells us her story of being an activist in the Iranian revolution of 1979, and the nine years of torture and isolation she endured in the dark cells of Evin Prison.

We lived under the crown of Shah’s monarchy. The depth of class distinctions and the absence of human rights made us drown in discontent. Behind the doors of my home, a political climate started. My brother was a Marxist activist, and preached about the oppression of the monarchy. He gave me ideological books that I absorbed completely as an untouched teenager. Studies in political science in the University of Tehran became my big political awakening. I decided to become an activist myself and joined a Marxist-Socialist organization. We fought for democracy and liberty of speech side by side with Islamists and Democrats. Our opposition grew bigger and the streets burned in the demand for change. Soon, the Shah stepped down from his shiny throne.

We knew what we didn’t want, but we didn’t know exactly what we wanted. The Islamists were better organized than us. Their march to power was louder, and in a moment our country could change radically. We could not imagine how their leader Ruhollah Khomeini would undermine our freedom even more. We, who had sacrificed our peace for the revolution, were now behind veil and forced to follow Islamic laws.

Women were banned from education and employment. Islamist propaganda meant that we didn’t belong anywhere except behind closed doors at home. We were pronounced the biggest enemy of the regime. It was a shock to learn that we had replaced something bad with something much worse. The lucky ones escaped the country. Others were jailed. You didn’t have to be an activist to be put in jail. They could arrest you for looking suspicious, just looking like you were against the regime. That could be based on wearing jeans. Even many school children were arrested. We were dissident people, and as the occupation escalated, mass arrests soon became reality.

1981. I was twenty-six years old. It was Saturday evening. I was wearing my nightgown and was about to sleep when the bell started to buzz. I hid under my blanket when they stormed in with their dirty purpose. About eight men, all armed. “Get dressed, you are under arrest,” they said aggressively. A boy who was only seventeen years old threatened me with his gun and led me to a Land Rover. In there I saw my brother and his wife. His wife and I would soon be separated from my brother. I didn’t dare to imagine that the next nine years of my life would be spent in suffering behind bars.

When I came to Evin Prison in Tehran, they put me in a corridor. It was full of women who were waiting for trial. Screaming from lashings thundered in our ears. I was pale and frightened when I heard the whip unstitch the skin of my sisters. After five days, it was my turn. And it would not be the last time.

They threw us in our cells, and the last prisoners they squeezed in as there was no more room for them. The nights were the worst. I was full of a heavy physical and psychological tiredness, and every night we had to sit up, squeezed among a hundred others. There was no chance for rest. Covered by chadors, we lived intimately, and were witness to each other’s anxieties and extremely violent outbursts of emotion. But we also learned solidarity. Many didn’t get money from their families. So we collected everyone’s money to provide all of us with food. There was no space to be egoistic.

I always got informed five days before. I stopped eating and drinking in the days before, so that I would faint out faster. I was told to sit down. I had to stretch my arm to the back over my shoulder, so that my hand was positioned between my shoulder blades. With my other hand I had to reach, so that the fingertips of my hands touched each other. They tied me like that. The pain traveled through my whole body. Time stood still. My muscles and sinews were being torn apart. For hours I sat like that. I started to sweat all over and it felt like I was on fire.

And they put a stinking rag in my mouth and started lashing. The wait for the next whipping was more painful than the lashing itself. At every breath, my body jerked. My intense breaths made the rag fall out, and suddenly my screams filled the room. Someone threw a blanket over me and sat on my stomach while holding my nose and mouth closed. I thought I was going to die. I did anything to breathe until I lost consciousness. The biggest punishment for non-believers was to believe. I’d rather have been whipped to death.

The guards did everything to break us down. When none of these methods worked, the coffins waited. There was a big room with hundreds of coffins. I was put there with a blindfold, forced to be completely still. Either it was a dark silence, or the Koran spread its propaganda from the loudspeakers. They fed our brains with whatever they wanted. We were convinced that we were already dead. And that the guardian was our God. Some could not stand more than five days before they gave up and become what the regime wanted. I was there several times, at the longest for six months. Monotony and solitude led to hallucinations and insane insomnia. I looked for anything to distract myself from that narrow world. But in the last days, I was near the end of my life.

The executions form the most horrific chapter in my story. One night, the guards took some of the prisoners. We were dazed and silent while watching this abrupt departure. A few days later, they took some more prisoners. One of them returned later. She walked fast in the courtyard under her chador and whispered something to her friend. We felt the fear in that corner of the yard. The guards came and took her again, that time forever.

It was around eight in the evening. The cell door was open. They told my sister-in-law to come with them. Soon she was back. Screaming and beating her head: “They are going to execute him.” Prisoners were executed through shooting behind our prison. We heard it, and counted the shots in silence. At half past eight the gunfire came. It was a very specific sound. Like a mountain that fell over the terrified souls of the capitulated bodies.

Followed by the most howling silence in the world: death. With every shot, the world perished. I counted the bullets in a whisper, “One, two, three.” I counted eighty-six shots that evening. One of them was my brother’s.

Death is the only dimension in life we can be sure about. But it’s a different feeling when you know that you can die any time because someone else has control of your destiny. To look on the bright side is the last survival instinct. They were laughing a lot when they got their death sentence. My best friend got hers a week before. Her dimples were permanent on her harmless cheeks in her last days. She wanted to leave her life with tender feelings to the last second. We were eating when they took her from us. The last thing she gave me was an angelic smile. A few minutes later, we heard the shots. It was the summer of death. In two months, thousands of opponents were murdered in silence. And still today this massacre remains in the dark.

In October 1990 I was released. It felt surreal when I signed the papers.

They stole my revolution, but I would never let them steal my mind. I never gave up my battle. Even through grotesque outrages where I was dehumanized, I refused to swallow it. I never regretted anything I did, as my actions didn’t cause any harm.

To forgive is not to forget. I won’t forget what happened in the 1980s in Iran: a huge crime against humanity. I will, as long as I live, write about it, talk about it, and inform people in every forum there is. Pass it to the next generation to create a collective memory, in the hope of never, ever again allowing people to violate the dignity of others so brutally.

In a war of resistance, we also get to know our shortcomings. We must compromise and correct ourselves. Self-criticism is the key to change. It is not only essential for each individual, but for the equitable system that we want to replace all over the world. The same brutal regime leads Iran today. Fighting and protest are the only options for freedom. My freedom had a high price. But it was the only thing I could do. Scream it louder.