By the time African refugees arrive in large Egyptian cities like Cairo, most bear the scars of physical and emotional abuse suffered in their countries of origin or during their trafficking across international borders. UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) caseworkers like 28-year-old Canadian Nadine interview and assess the needs and concerns of newly arrived child refugees in an effort to connect them with the supportive services they need in order to navigate an unwelcoming and inhospitable society. She explains the plight of African refugees in Egypt, the part she plays in the largely ignored issue, and the ways in which doing so has affected her own life.

My experience of working with challenging populations began back home in Canada when I volunteered with street youth. I remember feeling so incredibly out of place. I had no words for the first time in my life, and I sort of fell in love with the challenge of forcing myself to mirror the rawness of the children with whom I was working. There was no time or room to develop a persona with which I could protect myself from the pure, and often brutal, honesty I dealt with on a daily basis. I was immediately drawn to this intensity.

Pursuing this new-found passion in Egypt was somewhat serendipitous. I completed a postgraduate program in International Project Management and one of the options available for its requisite internship was in Cairo. I applied and, before I knew it, was accepted and on my way. I had never been to the country before, and soon found myself learning to acclimate to a host of cultural differences that would affect both my personal and professional life. Within a year of my arrival, and after the completion of my internship with an NGO focusing on gender-based violence within African refugee families, I began working as a caseworker for the UNHCR.

While official reports state that there are only about 51,000 African refugees living in Egypt, more accurate estimates place the number closer to 70,000. This discrepancy is due, in large part, to the reluctance of those who have fled their home countries from officially documenting their residence or intention to attain asylum-seeking status for fear of government reprisals against their families back home. These men, women, and children tend to come from Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia, and have fled poverty, warfare, and political persecution.

Nearly every one of these African refugees is smuggled or trafficked into Egypt illegally. As such, in addition to that which occurs in their own countries, they are also often the victims of further abuse along the way. Perhaps the most distressing of recent developments has been the emergence of torture camps in the Sinai for teenagers predominantly from Eritrea. These boys and girls hope to escape mandatory military conscription akin to slavery and, instead, end up kidnapped by Sudanese officials and sold to a string of Rashaida and Bedouin tribes upon crossing the border. Eventually, they end up in camps where their release is contingent upon their ransoming to their families back home.

From what case workers like myself have heard from survivors, the methods of torture vary. Some of their captors are well trained, and know how to cause the worst pain possible without leaving any physical scars. There are also those whose methods are far messier. One of the most common things we are told, and evidence of which we regularly see, is the use of burning plastic. Beatings, starvation, contortion, and suspension are also common. Every girl with whom I’ve spoken was raped at least once, and the boys are forced to watch. During any of this torture, the victims’ families are made to listen over the telephone.

Even when African refugees finally arrive in big Egyptian cities, they face challenges, discrimination, and hostility. Cairo is a difficult enough place for anyone, let alone for a teenager who is alone, hungry, suffering from physical and emotional pain, and probably doesn’t speak Arabic. Africans in Egypt have been attacked with acid, stabbed, beaten, raped, and evicted due to the colour of their skin. Not only do Egyptian law enforcement officers do nothing to protect them, but they regularly harass, detain, and abuse the refugees, themselves. To make matters worse, the country’s political instability and strained relationship with Ethiopia regarding Nile water rights have emboldened those who prey on African minorities.

Despite being a signatory of two United Nations Conventions on the Rights of Refugees resolutions, the Egyptian government offers these Africans none of the guarantees or protection it promises. These men, women, and children have no access to subsidized education, accommodations, health care, or even the legal right to work. Instead, they must turn to their own ethnic communities, charities, and NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) for support. Currently, it is my job to interview African refugee children without adult legal guardians. I listen to their testimonies and assess their needs in order to point them in the right direction.

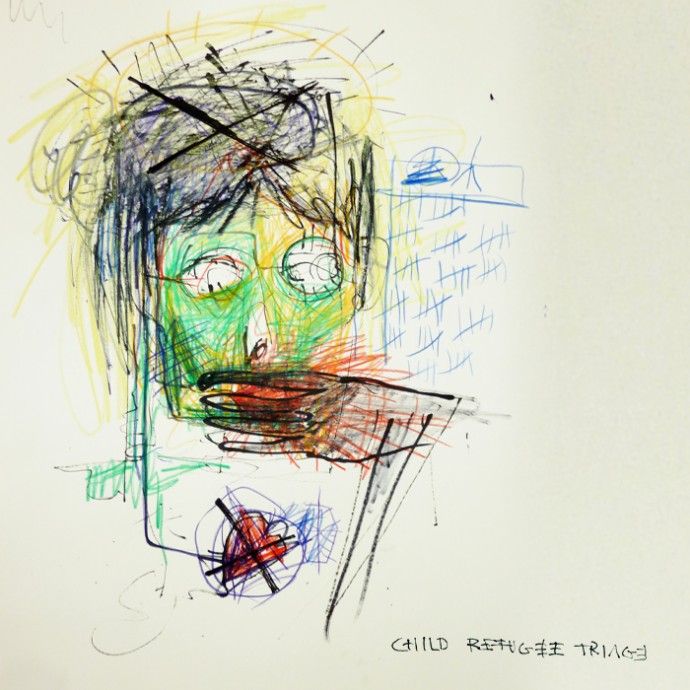

By the time these children arrive in my office, they are physically and emotionally depleted. With the help of an interpreter, I ask them for personal and family information, as well as an assessment of the reasons why they left their country of origin and what has happened along the way. This includes a detailed history of the abuse and trauma they have endured. I then determine, among other things, whether or not they need housing, adult caregivers, physical and/or mental health services, or connections with other youth close in age. Finally, I present them with an Refugee Status Determination appointment, during which they will meet with a lawyer at the UN office to determine whether or not they legally qualify for refugee status.

Being constantly confronted with the horrifying reality of these children’s lives on a daily basis has given me an insight into the concept of ‘vicarious trauma’. Hearing their stories is traumatic, make no mistake, but I struggle to feel confident enough to consider myself to be a victim. I tell myself that there is absolutely no reason for me to be upset. After all, I really have no right to complain. I was not the one that was abused, and I’ve had the good fortune of not having been held against my will in a torture camp. Nonetheless, I cannot deny the telltale signs of these children’s traumas having affected me personally.

I can’t stand to listen to the complaints of my friends anymore, nor do I allow myself the luxury of complaining or saying anything I consider non-essential. I’ve found that even basic conversation has taken on a new significance. I can’t be bothered to hear or speak about things that seem so trivial in comparison to what I discuss at work on a daily basis unless, of course, it’s in the company of my co-workers, with whom I share a deep sense of camaraderie and understanding. Nothing that I once felt was worth talking about really seems all that important anymore, so I rarely say much at all. There doesn’t seem to be a point to words that are little more than filler or fluff. This makes me feel very judgmental and condescending towards other people, and it’s not a quality I want to retain.

I also feel as if I’ve lost the capacity for pure, innocent joy. I doubt that I’ll ever again be as happy as I was before I began this work. These children’s stories don’t wait patiently in my office for my return once business hours are over. They follow me home, and I fear they will never leave me. I have recurring nightmares where either I am one of my clients being tortured or I am trying to save him or her from the same fate through physical intervention.

Not surprisingly, I often go through periods of complete emotional non-existence in which I’m incapable of feeling anything at all—neither sadness nor happiness. This sort of thing happens to every other caseworker with whom I’ve spoken, and I suppose it’s a matter of emotional exhaustion. After feeling so much, so often, and with such intensity, the emotive part of one’s brain can just shut off as some sort of survival mechanism.

Nonetheless, I’m not discouraged. Nothing is more rewarding than to be able to give others the opportunities to solve their own problems rather than adopting a ridiculous and degrading ‘white savior’ mentality and attempting to solve them myself. While I may be the one providing resources, my clients are the ones that consistently rise to the challenge and make progress on their own. To witness their dedication, commitment, and resilience is incredibly encouraging. Simply and selfishly put, the work I do makes me feel really good, despite the sacrifices I’ve made and the traumas I’ve inherited. Without a heart, or a passion for the person sitting across from me, there really would be no point. I plan to continue working with refugees until the moment I realize that I’ve stopped caring about my clients. At this rate, I can’t imagine this ever happening, no matter the personal cost.

As for African refugees in Egypt, things definitely seem to be getting worse. These men, women, and children are practically forgotten. This is, in no small part, due to the Syrian civil war and its own resulting refugee crisis. Nearly 135,000 Syrian refugees have fled to Egypt alone. While these people are certainly no less deserving of aid and assistance, the funding and charitable donations once committed to helping Africans has all but dried up as a result. It’s a case of compassion fatigue. The sad and unavoidable truth is that those whose wealth would be of tremendous service have gotten tired of watching Africans suffer. While I absolutely must maintain a shred of hope to be able to continue my work, I know that there simply isn’t enough money. Furthermore, so long as we address the symptoms of the issue, rather than go to its source, there can be no end. They will just keep coming.