Male artists dominate the electronic music scene. It’s overwhelmingly obvious. Of the factors that contribute to this dominance, one factor remains alarming: expectations from women regarding their behavior, interests, and skills.

Electric Indigo is an electronic musician, composer, and performer. She’s also the founder of female:pressure, a database for female artists in club culture, digital arts, and electronic music, which supports a network of over 1200 artists from sixty-one countries.

Electric Indigo, who gathered her the djing experience in the underground electronic music scene in 36 countries around the world, speaks to Sensa Nostra about the perspectives and challenges women face in the male-dominated electronic music scene, in an era highly influenced with digital communication and global collaboration, and the importance of female:pressure to the movement. She also explains why separation of genders in art is still present and how artistic minds can collaborate in order to combat the ignorance.

I grew up listening to mostly classical and jazz. My mother used to play records at home, and I still vividly remember waking up to Beethoven’s “Waldstein Sonata.” She also listened to jazz and swing classics: Glenn Miller, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday. I enjoyed the music a lot.

My older brothers took piano and guitar lessons. I also took piano lessons for three years and learn to sight-read classical music, though I never achieved the brilliance of my elder brother, whose ability to improvise blues and jazz harmonies, I absolutely admired.

I also remember my eldest brother taking boogie-woogie dance classes, and he’d practice at home with me. Spinning around with my brother as a child, I still love dancing to those syncopated rhythms.

In my teens, I started collecting records: hip hop, funk, jazz, and I was a huge Prince fan. My friends and I constantly recommended new music and shared mixtapes,—obviously, this still exists today, but, in the ‘80s, we just had different media, and mixtapes were my favorite—and, whenever someone would mention a new artist they liked, I’d find it and check it out. I had countless tapes recorded by friends, and I have away just as many tapes on which I recorded my favorite tunes, and it was this cultivation of musical taste, exchange, and accumulation that drove my decision to become a DJ.

I used to frequent a small, artsy bar in Vienna called Trabant, where the usual suspects of Vienna’s nightlife played their favorite records. There wasn’t even a proper DJ set-up, only two belt-driven turntables and some sort of volume control. As a regular customer and owner of a considerable record collection, I desired to play my music there as well. On one night, I went ahead and asked the owners to let me DJ. They agreed to, and thus my professional career started.

As a long-time female DJ, I deeply dislike discussions about cases of discrimination of female artists because I think that any valid argumentation is likely to perpetuate acrimony and complicate constructive solutions. It has never been my purpose to create separation of female artists from male artists just by being a DJ. Looking at line-ups, stages, DJ-booths, it becomes clear that the scene certainly has too little female presence. As a matter of fact, our intention is to create more diversity. Pretty much every artist I know has female and male (and possibly in-between, too) peers and allies, including myself.

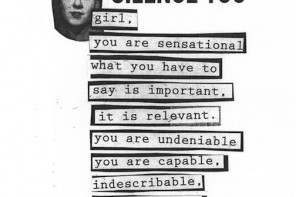

Still, the blatant stupidity and ignorance towards female artists is extremely annoying. A reputable promoter expressed concern, in The Wire, that raising the portion of female artists at his music festival would automatically mean lowering its quality. It felt like a slap in my face.

One of the most often heard arguments is that female artists are so hard to find. It means they need more exposure, and this is what I always wished to deliver. There is a lot of media work that can be done and female:pressure is my contribution to ensuring equal right in the electronic music scene.

The need for a source of information about female artists in electronic music was as obvious in the mid 1990s as it is today. I was not aware, when I started to DJ in 1989, that it might be an unusual thing to do. I got into DJing for the sake of music and my passion for beats, bass, and funk. Touring as an artist, I unwillingly created astonishment just because I am female. Starting female:pressure was supposed to help women become more visible and, thus, to grow stronger.

Female:pressure went online in 1998, but, at the time, it was only an html list. It wasn’t until I found the ideal partner, Andrea Mayr, who transformed female:pressure into an online database. Artists who join our network can use female:pressure as a tool for information, communication, feedback, support, and collaboration. The advantages of the emerging network are individually different, and I believe that the extent of what can be done with the help of female:pressure depends on the personal enthusiasm of artists. Personal contacts and common ideas about the scene, as well as shared aesthetic and musical preferences help to establish a new structure. We also offer services like regular gig postings, artist features, and articles of interest on our Facebook page. We help promoters to connect with female artists or organize workshops.

I always wanted female:pressure to be as open and easily accessible as possible. Since 1998 I have been maintaining the website and mailing list. I coordinated and managed projects such as our CD and DVD release, a tour in Japan, a sound creation platform called open:sounds that worked with Creative Commons. Last year, we experienced a distinct highlight in our activity: our ‘Facts Study’ came out, followed the Perspectives Festival that emerged from a group of female:pressure members in Berlin.

It’s through our members who keep female:pressure alive. New friendships and collaborations arise through musicians, our members, pursuing the same goals. For example DJs Xyramat in Hamburg and the Laminadyz in Vienna host monthly radio shows, and, as female:pressure members, often feature music from the community. Such face-to-face encounters between our members help to raise motivation and generate a feeling of emergence, in a philosophical sense. The joint effort, the larger entity, the interactions, and the feedback within the network all produce properties that are incredibly important for artistic refinement. I find information and knowledge about artists to be inspiring and positively challenging. I believe that cooperation is a necessity.

A great thing about electronic music is that, nowadays, it doesn’t need spacious equipment. It can be conceived and created wherever there’s electricity and a computer. With Internet access, you can quickly connect with like-minded people in many other parts of the world—or you can easily collaborate in “real life,” which obviously cannot be underestimated. Sure, cities like Berlin and London are electronic music hotspots. But these cities, especially Berlin, have room to test new boundaries, trial and error for new sounds, which I consider crucial for artistic progress and development. Through this, I also think that the chances for women to succeed as DJs are great in cities like Berlin because the intense level of awareness in DJ culture.

In the near future I would love to see female:pressure festivals. But in the long run, I expect female:pressure to become obsolete as a network for female identified artists, as I believe that a change in society is possible. Ideally, the structures built over time will be used as a support network.

I believe that equal opportunities for all sexes need to be ensured. Social diversity in general needs to be pursued. Structural barriers that impede participation of certain social groups must be dismantled. Therefore, we have to speak up and bring deficits to people’s attention.