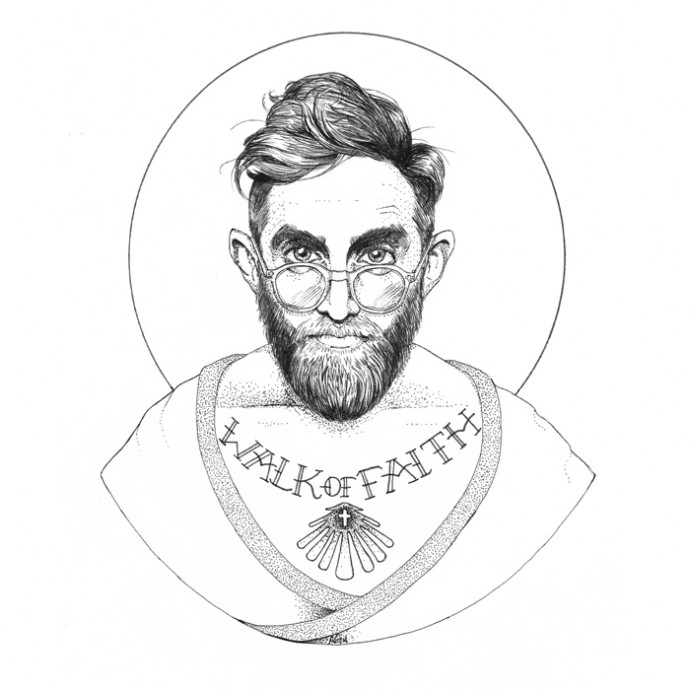

These days it’s hard to be religious. What once was the norm is now associated with fanaticism, shallow-mindedness, blind obedience, absurdity and intolerance. We talked to a person born into Catholicism. A metropolitan, a college graduate, a student of Medicine and Computer Science—the kind of person who ought to know exactly how harmful religion is to progress and mutual understanding, right? But instead he speaks to us about how a 300 km journey in the name of God reaffirmed his faith and his belief that agnostics and atheists might want to consider what they’re missing out on…

For twelve days we woke up at 5.30 in the morning, brushed our teeth, packed the laundry that was drying outside and maybe scarfed down some breakfast. We’d try to leave by 6am. In the morning we walked under the stars. You could see the moon, and it was dead silent. After 10 km we stopped for morning prayer. We sang. There were still 20–30 km before the next checkpoint. If you were fast, you got there at 3pm or 4pm. 6pm if you were slow. You got there, you ate, you drank, you popped blisters and collapsed in bed, and then you did it all over again.

The Camino de Santiago is a pilgrimage, a journey people take to the town of Santiago de Compostela on the western coast of Spain. It’s got this mystical origin. According to tradition, after Jesus died on the cross, James, or Santiago—same person—traveled to the Iberian Peninsula to spread the Gospel. When he returned to Jerusalem he was beheaded, and his corpse was put into an unmanned boat that crossed the Mediterranean and came miraculously to the western Spanish shore. A shrine stood nearby in the town of Compostela, where they entombed him. A cathedral grew around the shrine, and a city around the cathedral. People came to honor Iago, and the pilgrimage was born.

As with all pilgrimages, it was a physical enactment of a spiritual journey, a journey to God. You took as little as possible. No money, few supplies… you had to face hardship, you had to work. Now people do it for other reasons, not necessarily religious. For adventure, or for exercise or something. You still don’t take much. Just a backpack. Mine had a couple pairs of clothes, toiletries, sandals, a jacket, a little food, a cell phone for emergencies, money, detergent, pain killers, stomach meds, a water bottle, Powerade powder, and a knife. I ditched my sleeping bag on the trail. The typical starting point is in France, just north of the Pyrenees, but I started in the Spanish town of Léon, 300 km from Santiago.

Honestly I wasn’t feeling super religious before going. I’m a cradle-Catholic, a Catholic by birth. My whole life I’ve gone to church almost every Sunday. From an outsider’s point of view, there’s never really been a time in my life when I haven’t been religious. I’ve had a few truly religious experiences in my life, but, for a long time before the pilgrimage, I was a Catholic by the rites, not by belief and not by faith. Most of the time I just followed the rules without making any active effort to become, by the core values set forth by the Catholic doctrine, a better person.

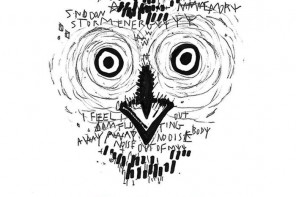

So I didn’t have a good reason for doing the Camino. It was a vacation, not a spiritual journey. Hang out in another country, visit friends… It sounded stupid. I could do other things with my time and money besides walking. The only other reason was this vague idea that I was searching for clarity. I had things swirling around in my mind: I’d just graduated from college, had devoted the greater part of the last few years to the MCAT and med school applications… I got into one of my dream schools and… I dunno, I turned it down. Then, after being focused on that one goal for so long, I had to reset my life.

And things started to take shape on the Camino. The trail became a metaphor for my own life. It has different stages, twists and turns, people you meet along the way. There are times when it’s really difficult. On the second day we walked 38 km. We started late. It was really hot and we were surrounded by desert. The walking wouldn’t stop. It just would not stop. People were crying. These past years—the sucky grind toward med school, not even knowing if I wanted to go—have been similar. Before I always projected into the future. These precise scenarios: I’ll go to med school, I’ll graduate with a bunch of debt so I’ll need to get a job. Where I get the job will be where I end up staying. I’ll start dating people around the area. I’ll probably get married there. On and on and on, driving myself crazy with speculation. The struggles on the Camino were hard, but they’re behind me, and now they don’t seem so bad. I guess that realization helped me see that all that med school stuff is the same. I can’t do anything about it. It’s in the past.

More than that, the Camino meant living in the now. On the trail you make decisions based on what you know in the moment, literally one step at a time. I didn’t have Facebook. I didn’t have internet. I just had to focus on what to do next and on the people around me. Walk and eat and sleep and pray and talk. It made me feel healthier. Not just the walking. Sharing stories along the way with people from all over the world. Look at all these people doing this for different reasons. It’s the perspective thing. Why freak out so much about all my crap? I understood one of the gifts of faith: you can just focus on what you’re doing, live well and honestly and with others, and put your trust in God that it’ll all be OK.

Ther Camino also gave me hours and hours of introspection, introspection in the context of my faith and how I could be a better person. I thought about pornography. I’d been looking at it. But I didn’t want it to be part of my life. I gave it up.

My lowest point—the worst parts stand out the most—was on the fifth day. It was one of the steepest segments of the trail, and I still wasn’t used to walking. I started slow and got slower. Time went on and pretty soon I’d lost everyone in my group. And we hadn’t even hit the hills! It was paved and flat, which somehow exacerbated the pain in my knee. I was so slow. It was depressing. And I still had most of the day to go. People I had never seen on the trail before started passing me. They asked if I needed help. But it’s supposed to be hard. I thought I could do it. Just had to warm up.

The difficulty and pain and isolation. I thought of my father. He’s sick. Crohn’s disease. Some sort of gastrointestinal failure. He doesn’t absorb the nutrients he eats. And we’ve been fighting. To him, turning down medical school was a stupid decision. I’m wasting my life. I’m falling behind. I told him I was moving to Vietnam to teach English. He just doesn’t understand. But he’s sick, and I need to work on our relationship. The adversity on the trail made me think about his suffering. It’s not that I was sympathizing with his misfortune through my self-imposed pain. I just thought I could offer my hardship as a prayer to God so that he might help my father, heal him.

But the pain was excruciating. I’d refused the help offered, and then I was all alone and would’ve given anything for some painkillers. I did the only thing I could do. I prayed.

In answer, an older German woman came trotting up to me.

“You look like you’re in pretty bad shape,” she said. I was the one in bad shape, and she’d had double knee surgery. “You might want to take a taxi.”

I asked her if she had painkillers. She’d just been to the pharmacy.

I started to feel better when I hit the elevation. The pain in my knee subsided. Different set of muscles I guess. I felt good. What was in those painkillers? I felt so good that I started jogging up the hills, and by the end I’d caught up with half of the group. It was fine and I was fine and I wasn’t tired, only hurt.

So I learned about faith. Well, I don’t know if learned is the right word. I didn’t learn anything like you’d learn a theorem or an equation. I experienced it. That fifth day was hard… A lot of people say that when you’re down, in a bad spot, when you have to deal with weakness and suffering, that’s when you need to believe in something greater than yourself to help you through it. You’d think it’s stupid, that it won’t work. But out on the trail thinking I couldn’t do it on my own, on a journey to God where belief was everything, it released me from my inhibitions to faith. God got me through the hardest moments.

I’m Catholic. I believe. I know people don’t agree with the Church. We sometimes joke about how being a modern Catholic is totally alternative, that we’re way less mainstream than all those self-proclaimed hipsters. But it’s not just Catholicism. People have a problem with the concept of faith in general. Isn’t it too easy to just believe whatever doctrine is given to you? Doesn’t it foster stagnancy and intolerance? It’s not easy. People challenge my beliefs every day. I constantly have to reconcile the doctrine, my experience and what people tell me. I think people today are too self-centered. When you make your own moral code, it seems too easy to revise it to suit your ego, to justify selfish choices. Plus you’re always changing. It makes it easy to have existential crises, to be pushed to nihilism or to waiver in ambivalence. You have to live some way. Faith is an anchor point, and always reminds you to think outside of yourself. I tend to doubt my own reasoning. The strength of a religious doctrine is that it’s the result of years and years of reflection, and I prefer to stand on the shoulders of giants than all alone.

We’re too caught up on the hot-button issues, abortion, contraception, gay marriage… People forget that the number one tenant of Catholicism is compassion. Out there on the trail, compassion led pilgrims to understand each other, to listen to each other’s stories and gain perspective. There’s definitely intolerance today, but it’s a misapplication of faith, and goes both ways. I know that the Church has been wrong in the past. It’s imperfect. But I choose to believe that the Church’s right and wrong is THE right and wrong. That doesn’t mean we need to go around chastising people. We need to understand each other. The truth will come to light with time.

When we reached Santiago, it’s hard to say what I felt. The end. Relief. Sadness. Happiness. There was still the question: what comes next? But I was peaceful.