Mirza, 29, is a Berlin-based bar owner. Born in the town of Cazin, in the northwest corner of present day Bosnia and Herzegovina, his first memories are of growing up in the midst of war. Following the nation’s successful independence referendum in 1992 after the breakup of Yugoslavia, Bosnia was thrust into a notoriously horrifying conflict fought largely along ethnic and religious lines. Mirza describes living in a city gripped by the routine of war, though far from the worst of the fighting, and how being a child shaped his perspectives and understanding of this reality.

I don’t really remember much about Cazin before the war. Though I suppose it was as fairly typical and boring a small town as it is now. I do recall witnessing, but not understanding, the deteriorating political situation because of what I saw on television. As kids, my younger brother and I were fascinated by the explosions we saw on the news, but we didn’t ask too many questions. All we knew was that bad things were occurring somewhere nearby.

My parents began stockpiling food and supplies, and the general feeling was that we were waiting for the inevitable moment when what we saw on television would reach our town as well. Everyone was worried, but to a child it was thrilling. All I could think about was how exciting it would be to finally head down into our apartment building’s improvised basement shelter and begin eating the sweets that were amongst our untouched provisions.

The general consensus, even among the older people of our community who had already lived through war, was that a full-scale, long-term conflict was unlikely. Instead, it was assumed that everything would settle down within a couple months and things would return to normal. There was a faith that our collective identity as Yugoslavs would trump any other ethnic or religious differences and would ultimately prevent us from fighting amongst ourselves.

Soon enough, however, the war did reach us. It quickly became as inconceivable to imagine it ending as it once had been to imagine it beginning in the first place. The economy completely collapsed. We lost electricity, there was no work, and no longer any food available other than what little we received once a month as humanitarian aid. Along with every other male over the age of eighteen, my father was conscripted by the Bosnian army. By some stroke of luck, he was employed in civil services instead of fighting on the front lines. Nonetheless, he would be gone for weeks or months at a time. We never knew where he was, what he was doing, or whether or not we would see him again.

I’m embarrassed to admit it, but I remember being jealous of those children whose fathers were killed in the conflict. Try telling any seven-year-old how it’s fair that those children without fathers were the first or, on some occasions, the only ones to receive humanitarian aid. They were often given warm clothes and new shoes, and their families were celebrated for having made the ultimate sacrifice. I needed clothes and shoes, too! No amount of my mother’s explaining made this any easier for me to understand.

I remember quite vividly the first day that Cazin was shelled by the Serbian army. I was playing outside our apartment building with my best friend. We heard the sound of distant, muffled explosions, and the ground rumbled beneath our feet. Too mesmerized to be scared, we stood listening. Suddenly, I spotted something arching towards us across the sky. Having never seen an artillery shell before, I was transfixed by the object as it drew close enough for me to be able to make out its shape. It crashed into the ground somewhere behind us. The concussion rattled my body, shattered the windows of nearby buildings, and showered the streets with glass. Coming to our senses, we ran back to our apartments, anxiously laughing and joking that we probably wouldn’t see one another again.

The first explosion of an artillery barrage was always the most frightening, as there was no warning. Immediately thereafter, my mother would run to the balcony of our building. While we were not supposed to stray out of view, we often did so anyway. If she couldn’t see us, she would scream our names. Until she caught sight of us, she didn’t even know if we were still alive. But then, of course, as soon as we would return, she would want to kill us for worrying her!

I still don’t know how my mother managed. She was as old then as I am now. I can’t even imagine raising children by myself in the relative safety of present-day Berlin, let alone in a small town during a war and without an income, food security, or coffee and tobacco. Making sure that my younger brother and I were fed and safe was a daily struggle. Once the shellings began occurring regularly, she was constantly anxious and shouting at us. To keep us indoors meant that we would yell and cry and drive her crazy, but to let us out meant risking our lives.

Though I knew what death was, having become familiar with the concept from watching movies and television, I never believed that it was something that could happen to me or any of my loved ones. It simply wasn’t possible to imagine someone close to me being killed. Parents, especially, are such a constant and concrete presence in a child’s life. Even when a classmate of mine was killed in the shelling, I never doubted that we would survive.

Despite the danger, everyone soon learned to live as normally as possible under the circumstances. Though we were always afraid, even us children grew to be able to suppress our fear in order to function and maintain somewhat of a routine. Life just went on, at least in whatever ways it could without work and with an evening curfew. Sure enough, within two years no one could be bothered to go to the shelters anymore when the town was shelled. The older members of the community resigned themselves to a sense of fatalism, and besides, it really was a hassle.

Because Cazin was predominantly populated by ethnic Bosnian Muslims and fell within the Bosnian controlled area of the country during the war, religious classes soon were implemented in schools as a way of encouraging solidarity and cementing allegiances. Though my family was historically Muslim, my parents are secular. They raised my brother and me to appreciate and participate in celebrations, but not to live by any rigid set of religious rules and regulations. I soon realized that these classes weren’t really about examining and learning about Islam so much as about instilling fear in us.

I was taught that I would burn in hell for eating pork, not fasting during Ramadan, and even for having friends who were non-Muslim. I remember that there were three children in my class who weren’t Muslim. They were made to sit outside and wait while the rest of us were told that our religion was ‘right’ and theirs was ‘wrong.’ Even as a kid I recognized all this as propaganda and I hated it. My teachers didn’t like that I was always asking questions. I was only supposed to listen and to agree.

As children, we were really only interested in having fun, anyway. On good days, we’d go to school. On bad days, we would be happy that the shelling meant that we didn’t have to. After a barrage, my friends and I would run off to the place where it had occurred. We made a competition out of finding the largest pieces of shrapnel. Despite the danger, we were confident (or naive) in our ability to distinguish shell fragments from unexploded ordnance and cluster bombs. Our childish superstitions added a guilty thrill to the game as we were somehow convinced that bringing these pieces into our homes made them, in turn, more likely to get hit.

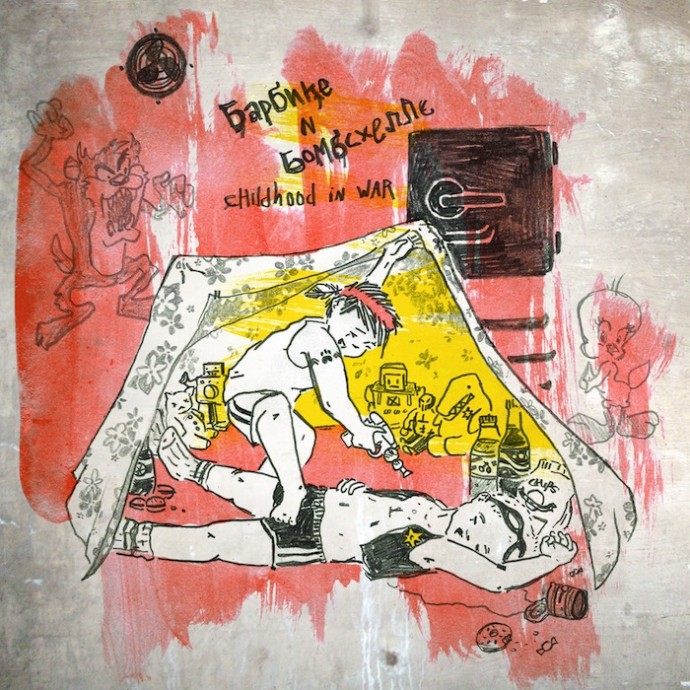

Other than by playing outside, and without electricity or access to toys and gadgets, I was left with the escapism of books and my imagination to entertain myself. I’ll never forget how jealous I was of a neighborhood child who had a real Barbie. My friend and I made dolls by dressing strips of wood in scraps of cloth and using dandelions as hair. Though, as luck would have it, one day my family received a care package from European children. Inside was a real Barbie of my very own! It was probably the greatest moment of my childhood.

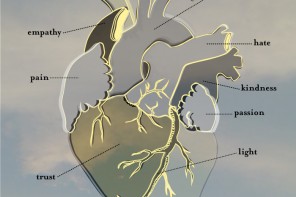

It’s recollections like this that remind me just how happy my memories really are. The conflict taught me, at a very young age, the value of fun, family, and friendship. Whenever fathers returned home for a couple days, people would celebrate. Precious bottles of booze that people had been keeping for such occasions would emerge, and everyone shared generously with one another. War really does bring people together. Sadly, this often occurs for all the wrong reasons, but it also can happen in very beautiful ways.

I’m convinced that being so young was what kept me from becoming traumatized. No matter how bad things got, I was either fixated on my own childish self-interest, incapable of grasping the total reality of the situation, or too busy having fun for it to have affected me as much as one might assume. That being said, I’m extremely lucky. My story isn’t a sad one. By the time the war eventually ended and people began to pick up the pieces, I hadn’t lost a single family member or loved one to the conflict.

Though it may have been luck that got me through those years without any serious physical or emotional scars, I do owe a lot to my parents. They raised my brother and me in a way that challenged the ethnic and religious zealotry that arose during the war and has since infected the country. They bravely taught us not to hate anyone, not even those who may have been trying to kill us. Unfortunately, it would appear as though we were the exception. Though the war may be over, the hatred remains. The very ethnic and religious divisions that were once viewed as secondary to a shared sense of identity have since become the standard, and it’s enough for me to have realized that I could never live in my home country again.