As our lives are spread thinner and thinner, are we losing a sense of what truly matters? Is the lack of real physical interaction and our use of social media driving us further and further away from happiness? Philip talks to Sensa Nostra, ruminating on loneliness and the way that we deal with relationships in a digitised world.

Tea bag in the cup, the kettle pops. In goes the water, piping hot droplets trickling down the spout and onto the floor. You shift your toes to avoid the scalding heat, place the kettle back in position and vacantly stare into the cupboard, momentarily forgetting that it was the sugar you were looking for. You apologise to yourself for being stupid and forgetful then spend the next few seconds wondering why you just apologised to yourself for being stupid and forgetful. Plonking one-and-a-half teaspoons of sugar in the browning liquid you convince yourself that wasn’t actually a half spoon and chuck in another few dozen granules just to be sure. Then you remember that one time you were told you make your tea all wrong and the milk goes in first and you make a pact with yourself to do it right tomorrow, that today you won’t care because caring is hard work and you’re feeling slightly nauseated.

Sitting down in front of your laptop you click open your usual tabs. Social media, emails, news. Checking for something special, you pray that nothing has happened. You watch the vapour rise from your cup, questioning whether putting some cold water in it to make it an acceptable temperature really is that wrong. It probably is. You tentatively sip, pleasantly scalding your top lip. Is it too early to have a cigarette? Most likely, but you roll one anyway—giving up is something you will do when you’re ready and today is just not the day for it. It’s cloudy, the cars in the street are growing in number, their obnoxious rattles and Doppler-effected, tinny pop beats coupled with the incessant drawl of overhead aircraft conspire to deny you any form of peace. Inhaling the cigarette, your throat constricts and head feels heavy. Reels of blue-grey smoke drift hazily towards the window along with half of your breath.

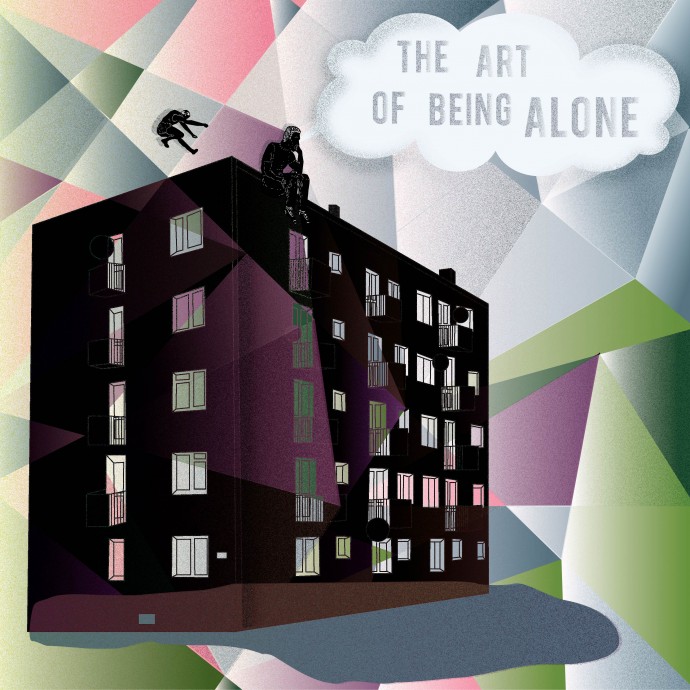

So you sit and wonder what you’re going to do. What kind of day is this? I could finally do the washing, or clean my room. Perhaps I’ll look for some more work, or write something. Maybe I’ll go out into town and have a drink and watch all of the people doing all of their things. Check out that gallery, or take a walk along the South Bank. None of it appeals—it’s just going to be you somewhere else, you might as well get on with yourself here and save your mind from the boredom of public transport or bombardment of adverts and the compulsion to spend. Let’s just stay in and send out a post on Facebook, see how many people care. Retweet a celebrity on the off-chance that fame is like a transfer tattoo. Check those emails over and over again hoping for anything other than Hungry House reminders and Booking.com offers.

This is loneliness.

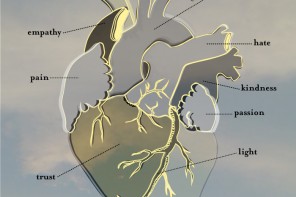

The unforgiving realisation that no matter what you do, you’re just another soul trapped in this flabby body with hands and feet and loads of those organ things inside of it that, really, you don’t want to be thinking about. You will sigh, close your eyes, scratch your head or look up to the ceiling, all the while the simmering arguments of unrest and desirelessness contort your brain into a pulsating mass of whimpered wants.

Wholly uninterested in the deepening hole of “I’d likes” and “I fancies,” you wonder, “What do I need?”

I once had a girlfriend who worked in a shopping centre. She was one of those people that would stand smiling, hands behind their back, an eagerness in their eyes, just waiting for you to pass so they could sprightly ask, “Excuse me sir, could I interest you in a massage?” The kind of person I, and many others, would avoid at all costs, checking your step and throwing them a look of wounded despondency that shows just how much you object to their neediness. Not everyone’s like this, though. She did get customers, and I once asked her what kind of person gets a massage in the middle of a busy promenade.

In the distinctly wonderful way only she could talk, with her elbows placed on the table and a lit cigarette held firmly between her spindly fingers, she answered with something that resonated deeply inside of me. There was a sprawling demographic that ranged from blokes who were sick of trundling around the shops to kids who thought it was funny. However, it was her observation on the lonely that struck a chord. In her almost-perfect Nordic-English she professed that for a lot of people the reason they stopped is in order to be touched by another person.

“What?” I asked.

She inhaled, flicked the ash from the fag into a turquoise ceramic tray, looked down at the table and ran her free hand across the top of her head. She then continued with such earnestness that, still to this day, makes me wonder why we ended up hating each other so much. It was her experience that a lot of the people who would stop—those that did not check their step or throw her despondent looks—were the men and women for whom actual physical interaction was a rarity. To actually be touched by another human being is extremely important, but is something that most will take for granted. After all, we are coddled from birth, pressed against our mother’s breasts and held gently in our father’s arms. We are, from the second we are conceived, wrapped in the warmth of another, and as our lives develop we find ourselves drifting in ever decreasing circles and floating on wider berths. Then she stubbed out her cigarette, told me she was going to have a shower and left the room.

We lived in one of those ceaselessly evocative relationships, bred on the extremes of emotion. My hand caressing her neck turned to noose and her nails along my back to daggers, only to once more wilt and become tender when burgundy rage had subsided. I believe, above all else, it was our physical interactions that kept us together, be it tooth and nail or lip and tongue. The fights and arguments and hurtful gut-wrenching sentiments that lay thick in the air throughout our house were detonated and smothered by our own yearning to feel connected with one another, and it seemed as though we fought to beseech each other’s worn watchtowers and clamber into each other’s bodies, breaking each other down so that we could rebuild together. Though by the time it came to reconstruction we had, like the typical brickie, lost interest in our projects and felt like there were more important matters to attend to.

I slept with this woman every night of the week, our limbs intertwined. We inhaled one another’s breath throughout the dark hours until, in the morning, the sun ruefully ripped one of us from our hallowed cradle and back into the world outside. The days felt long in their passing, and fruitless in their meaning when, apart, we would work our jobs and fumble around through our waking lives. Though the days never felt so long as they do now that we’ve separated, when the first thing I see in the morning is the litany of month-old, scrunched-up teabags and spoons that litter my windowsill.

As with our relationship, so too has life become increasingly diasporic. With fettered veins of our meandering consciousness spread throughout our Facebooks and Twitters, text messages and thoughts—we are cultivating a certain climate of disconnect, delving into multi-dimensional social networks that drive us further and further away from what it is we truly need. Our desires for validation are rapidly delivered by the click of a button, and our need for attention is quelled for a few minutes until we remember that we’re unhappy. The worry is that as this cycle continues we will fall prey to the machinations of being lonely and become victims of an on-demand society. Our digitised lives are causing a greater chasm between us, replacing how we understand our emotions with a numbing morphine-like drip of social interactions. With this phenomenon becoming an undeniable fragment of the human psyche, I believe there is one thing we need to remember:

Loneliness is natural.

It is your body’s response to a lack of real and necessary human interaction. For some it seems like an insurmountable fortress—in most cases, one which has been built around them, brick by brick, from birth—for others it might feel like they’re on the outside looking in. The reality is that as much as we crave the feeling of reassurance, which we can only get from another person, we’re frightened of what opening that drawbridge might deliver. Charging through the gates may be the apparitions of jealousy and hatred, lance in hand, aimed directly at our hearts. It is your responsibility to remember that these things are fictitious analogies, driven by fear—and that even they, in their horrifying pomp, are nothing but figments of your imagination. The need to be touched and to feel your skin on another’s is far more important and should hold far more weight than that faux sovereign of mental anguish, insecurity. The only way we can be happy is to cede him no ground, and crush his petty decrees with the affirmations of what truly matters in life: the kisses of a lover, meeting eyes with a stranger, talking to a pensioner. The list goes on.

So get up, clean your room. Go outside and take a walk. Meet people, talk to strangers—travel somewhere. Have lunch on a double decker bus and only take bites when an old person gets on or off. Have a chat about your favourite Sly Stallone film with a drunk. Throw rocks at Foxtons or Sainsbury’s and cackle about it as you run away, then pee in a bush. (Personally, I’m going to start by getting rid of my tea bag collection—the smell is indescribable.) Just do something other than sitting around wondering what you can do and refreshing your homepage every five minutes expecting something to change.

Pingback: Technological Burnout | pdcdigital()