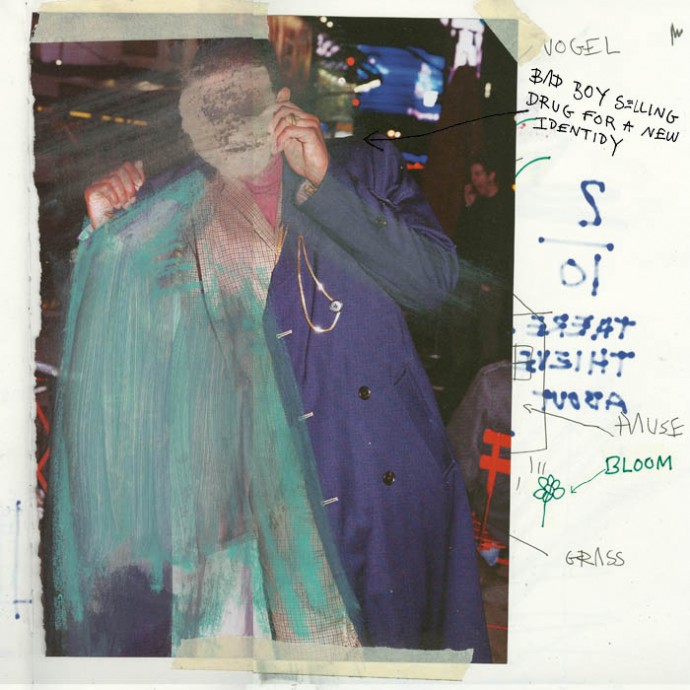

It’s very easy to be influenced when you’re thirteen. Especially when you’re a self-conscious little boy from the suburbs, with no problems, no fraught history, no mitigating circumstances. A teenager’s affect and emotions can be very easily manipulated, particularly when all he’s ever known has been his suburban tarmac and his thug idols. At a time when the ‘society of the spectacle’ reigns supreme, the message addressed to such teenagers has never been so confusing. Artists portraying dealers as heroes, robbers as messiahs, and prison as an initiatory journey can deeply affect adolescents looking for a meaning in their lives. Pierre first started to sell drugs, like many others, to be accepted by his peers, but also because the media declared that dealing was cool.

My name is Pierre; I am French and I am white. When I was young, I didn’t like France or my identity. I was anti-white. I know that sounds pathetic, but what we were learning about France in history classes, especially about colonisation and slavery, didn’t make me comfortable with being white. Everyone at school was inventing some alternate origin for themselves. I didn’t want to be the little white kid at the top of the class. While my classmates were busy inventing their new backstories, I was also creating my own new identity: that of a drug dealer.

I was nothing but a little jerk. A little thirteen-year-old jerk who sold pot to show off in front of his buddies. There is nothing fancy, sensational or exciting that could explain my pathetic career plan, or even make an interesting story out of it. There is just the astonishing banality of a little jerk who wanted to grow up too fast and be someone else.

I grew up in a suburb—maybe, more aptly, a ‘slum’—called Le Quartier des Quinze, a district of Strasbourg, which, like every slum, has its codes. The feeling of being stigmatized, excluded, discriminated was omnipresent. That being said, it was a quiet slum, where there was no real social or economic misery. The only real misery was ideological.

Like most suburban kids, I wasn’t doing much but smoking pot and hanging out. I started selling because I found the image of the drug dealer attractive, appealing. At the time I was listening to rap music in which dealers were considered to be above the rest, deserving some kind of so-called respect… All my ideas and principles were built on a series of misconceptions. Everything was fake from the start, both my outlook on the world and the values I thought I should be supporting. I built myself a doomed future. My standards became the opposite of what I had previously defined as ‘good’ or ‘right’.

When I was fifteen, I expanded my repertoire and started selling junk. I went up in rank in order to raise the adrenaline, but also, especially, to do ‘better’ than my mates. I was making a lot of money, but that wasn’t the appeal. It was just to show off. Believe me, most dealers have the same motives as I did. They simply victimise themselves and hide behind so-called financial miseries to justify their pitiful actions.

All rap songs that were broadcast on TV at the time justified the daily mess in which we were stuck. A jerk like me could only fall into that trap and take the message seriously. I really believed that we could live well, only by dealing drugs. While we were dealing heroin, famous French artists like Booba, having flung that message at us, were more than comfortable in their easy, laid-back lifestyles in Miami. There are so many young people in France who fucked up their lives because they let themselves be deceived by the widespread Manichean discourse in the media. If I screwed up my life, it is because I was listening to this message all day, every day. And because I was stupid, of course. My CD drive reminded me that dealing was cool, that there were no consequences, that prison made you a tough man and adorned you with a ‘certified gold’ label.

I didn’t want to be who I was. I wanted to be someone else, so I became a drug dealer. I created a new world for myself, above the law, above society, and above good people. I despised everything. I was a living stereotype, an argument for the electorate of Le Pen. In my world, the more stupid you were and the more you destroyed yourself, the better your image became. We used the famous couplet: “I saw everything. I know everything”. He who was greatest would shout it the loudest.

People need to suffer. They are empty so they create a reason to suffer, a reason to ruin their lives for good. I needed to suffer. Suffering was ‘trendy’. I was pleased with myself for that reason. I felt strong and I was not afraid of the consequences. As a young person, I did not have a fully developed neocortex, and it’s that specific part of the brain that relates to perceiving consequences. I just believed that not thinking of them was seen as a proof of courage. It was only when I grew up that I realised the consequences and they came back to bite me. One day, the cops came to my house. I had been snitched on. They wanted to dig through my stuff a bit. I was screwed. Once again, nothing mind-blowing; even my fall added nothing spectacular to my banal career as a dealer.

I then had a ‘choice’: psychiatric hospital or prison. So I picked the six-month therapeutic order option. It was long, boring, annoying and noisy, but in the end, quiet and life-saving. At the time I was thinking that I should have gone to jail; it’s true that in prison you can be quite comfortable: you can smoke pot and you can even get a TV and a PlayStation. Although I spent quite a long time there, I can hardly even remember how the weeks rolled by. It was a long and slow boredom that spread over those six months. Days were alike; weeks blurred. To escape the boredom I started to read.

I met with the psychologist and the doctor twice a week. The rest of the time, I exchanged few words with nurses. They were nice but did not have much time due to understaffing. I was meant to, but I didn’t want to speak with the doctor’s assistant. She was only a few years older than me and so I didn’t feel enough real distance to be comfortable. I found it humiliating to tell her my problems.

Isolation saved my life. I was face to face with myself, alone with my stupidity and with the youth I had just wasted. It took me some time to realise what my time in the hospital was giving me, the mutation that was taking place. At first I perceived it as a void, but that void filled me with great insight into who I was, what the world was, and what society was.

My eyes were open, but I was still restricting myself to my old ideas, and indeed, as soon as I was out, I started selling heroin again. But I continued to read. The exercise of comprehension I had started during my internment continued on. This search for meaning and the quest to understand what our society was built on saved my life.

Today I have come out of all that. I no longer sell or use drugs. Nevertheless, I still have to face my own reality: the reality of a naive kid who allowed himself to be fooled to the point of becoming a black sheep, but a sheep anyway. The result of my stupidity is far from bright: I do not have any qualification and I will never get a decent job. It was an indelible folly, an irreversible wrong step, a silly mistake that cannot be repaired socially or physically.

Most of the people I knew at the time when I was dealing are now security guards at supermarkets; some are in jail, and some others have become Islamic radicals. Only a few of them came out of that shit young enough, in a smarter way than I did, to make something of themselves. Those people probably don’t want anything to do with me, and I don’t blame them. Who would want to hear from that little jerk? I wouldn’t either.

The whole experience has irrevocably transformed both my mind and my body, even if it’s not always obvious on the outside. And all this, for the sake of what?