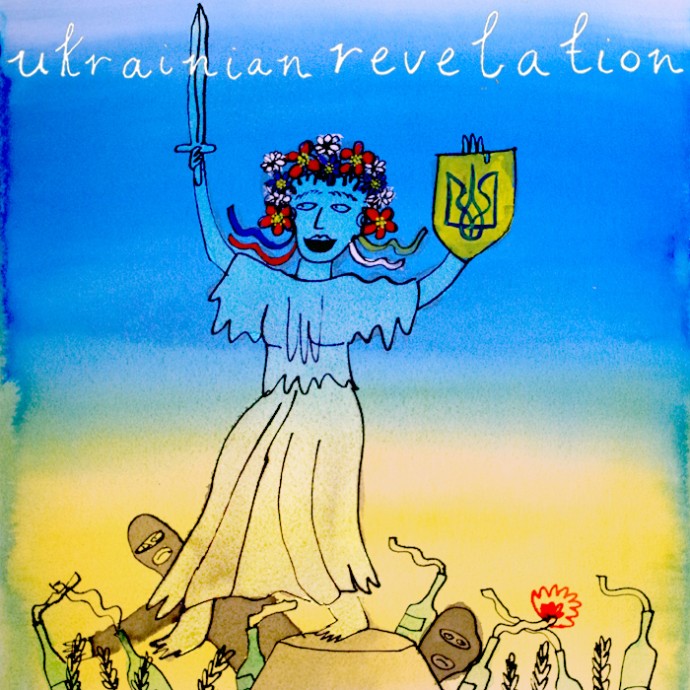

In January of 2014, the Maidan revolution in Ukraine took a violent turn when the special forces of the police attempted to suppress the protests using force. For a week, masked protesters, armed with Molotov cocktails and sticks, waged heavy battles with police, winning, and forcing the president to the negotiating table. The media was quick to attribute the violence to Neo-Nazis, and fear and doubts were voiced concerning the revolution’s possibly fascist nature. Yuri Leiderman is a renowned writer, filmmaker and conceptual artist. As a Ukrainian intellectual of Jewish and Russian origin, he offers a surprising perspective on fascism in Ukraine.

I was born in 1963 in Odessa, in the southwest of Ukraine. It’s a completely Russian-speaking city. My ethnic origin is Jewish. When I was born it was not Ukraine—it was the Soviet Union. It consisted of fifteen socialist republics, which were absolutely artificial theoretical entities. It was the so-called Ukrainian Socialist Republic, but nobody took it very seriously; it was all just the Soviet Union.

Growing up, my family, my friends, and all the friends of my friends were Jews. We were absolutely secular. We did not practice our religion, but nevertheless there was a strong sense of being Jewish, because of state anti-Semitism. As a Jew, you could only get to a certain level in your career. If you were an engineer, the most you could be was the boss of an office, or chief of a department, but you would never be the director of the factory. Maybe you could become head engineer if you were only half Jewish. This made us feel a bit separated from the rest of society.

With the fall of the Soviet Union, institutionalised anti-Semitism as good as disappeared. I remember watching TV on New Year’s Eve of 1999, and seeing the drunk Russian prime minister, Viktor Chernomyrdin, dancing a Jewish dance to the most famous Ukrainian Jewish folk song, being played by a military marching band. This was a sign for me that state anti-Semitism was a thing of the past.

There was, of course, some anti-Semitism in our lives. When I was a child it would be a bit painful sometimes. Another kid might say, “You fucking Jew!” and I would say back, “You fucking Russian!” That sort of thing would happen, but mostly between children. There were some proletarian areas in the bigger cities, which were supposed to be more anti-Semitic. If you went there something could happen to you, but these were just generally dangerous areas. Someone who wanted to beat or rob someone might use Jewish ethnicity as an excuse, but I can only think of one instance where something like that happened to someone I knew. I look very Jewish and I spent time in proletarian areas, drinking in hardcore proletarian pubs, filling our glasses up with vodka under the table. It was interesting for me, and I never had any problems. Of course some drunken person might say, “You are a Jew—yeah!” and maybe someone would make a joke about it, but that was the extent of my personal experience with anti-Semitism. In everyday life, I didn’t feel threatened, scared or discriminated against by Russian or Ukrainian people.

People in Russia and Europe are worried about fascists in the new Ukrainian government. I am not afraid. I have been following the revolution very closely. I read the papers. I watch a lot of interviews on the Internet. I read the manifestos of the parties. There is so much propaganda. Let’s take the infamous militia Right Sector, for example, who played a decisive role in fighting the police in Kiev. Friends from Moscow tell me they are Nazis. What do they base this on? The manifesto and agenda of Right Sector is available on the Internet. I have read it carefully, and I see nothing Nazi about it. It’s a kind of moderate nationalistic, patriotic party, which exists in any country in Europe, usually supported by a small minority of the people.

In Odessa recently, pro-Russian provocateurs vandalized the Jewish cemetery, defacing graves and leaving behind the insignia of Right Sector, in an effort to turn locals against the revolution. Members of Right Sector helped local Jews to repair the damage, and as a paramilitary group, swore to protect the Jews of Odessa should there be further acts of anti-Semitism in their communities. They also took part in the funeral of a Jewish fighter from the Heavenly Hundred, one of the protesters who was shot by the police during the protests. What kind of Nazis are these?!

Then there is the conservative right-wing party Svoboda, who won 10% of the vote in the last election,and are one of the three parties that make up the political wing of the revolution. Their leader, Tyagnibok, has been criticized for his anti-Semitic rhetoric. They are a right-wing conservative party, it’s true, but their anti-Semitic tendencies have been exaggerated. There have been one or two sentences that could be considered offensive, but they are not as anti-Semitic as they are being understood.

Most of the controversy revolves around one word, and that is the word Jid. In German it is Jüde, meaning Jew. In German it is not offensive. In Polish it also means Jew, and it is absolutely neutral, because there is no other word for the Jewish people. In Ukrainian it sounds offensive, and in Russian it sounds incredibly offensive. Once or twice it may have happened that this young politician from Svoboda, Tyagnibok—feeling a bit provoked—referred to somebody as a Jid. This is definitely inappropriate for a political leader, but knowing that he comes from the border of the western Ukraine and Poland, which has a neutral attitude towards this word, I think it could be understood and forgiven.

The Russian media fail to mention that Tyagnibok was interviewed by the Israeli press several times. I’ve seen those interviews. He was questioned about his anti-Semitism, and the Jewish and Israeli media were by and large satisfied with his answers. How Nazi and anti-Semitic can we call Svoboda, when they have members working in a coalition government with a prime minister of half-Jewish origin, a vice prime minister of fully Jewish origin, and helping to appoint Jewish governors to govern various cities. It’s a kind of schizophrenia!

This may sound a bit strange coming from a person of Jewish origin, but I quite sympathise with the Svoboda party. I sympathize with them because they are idealists. I like people who act according to ideals. During the twenty-two years of Ukrainian independence, again and again we have seen politicians who change sides and opinions very quickly according to the conjuncture. I think there is more of a guarantee with parties like Svoboda that they will not simply change their mind to get ahead in politics.

I see nothing dangerous in Svoboda. They are clearly a conservative party, and many of their opinions are different to mine—they want religion to have a role in the state; they have some homophobic tendencies; they have some tendencies towards conservative education and religion in schools—but these things are just parts of a conservative political agenda. You can agree with or disagree. I hope when the Ukraine is stronger, more liberal people can discuss these subjects with Svoboda. There are many humanitarian and cultural subjects on which I would not agree with this party, but there is no reason to be afraid of them. They are absolutely normal Ukrainian patriots.

These parties exist because people need to make some sense of life. Western European liberal governments endlessly debate whether we should tax 15% here or 16% there. This sort of national discourse does not satisfy the people’s maybe-even subconscious desire for a national identity. What does it mean to be German? What sense is there in the German way of life? What does it mean to be French? Liberal parties don’t offer answers to these questions.

Right now in the Ukraine we have just experienced the birth of a new national identity. I am talking about a positive sort of nationalism. The border between healthy and unhealthy nationalism is a blurry one I know, but maybe in the Ukraine this border could be investigated and shaped. This will require a lot of work. What the people are doing now is very easy. Singing the national anthem, speaking in Ukrainian, waving our beautiful blue and yellow flag and putting up pictures of the fathers of the Ukraine. But there is a big job ahead—for the historians, for the artists, for the cultural activists—to try to take out all the propaganda and myth from these slogans and symbols, to begin a more realistic dialogue about what it is to be Ukrainian, whether you are Russian speaking, Ukrainian speaking, ethnically Russian, Ukrainian, Jewish or Tartar.

The memory of the revolution is really a kind of mourning and celebration of its victims. They have united the country. They are our heroes, and in front of our heroes we want to be a little smarter, a little braver, and more ready to listen to each other. This is the common spirit in the Ukraine now.