We interviewed a guy that comes from one of the most mysterious countries in the world to us in the West today. To emphasize this, he starts off by explaining that most people think when he is introducing himself that he actually is pronouncing Pakistan incorrectly. But in fact, he knows how to pronounce his country, Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan is one of the most hermetic and undisclosed realities of central Asia–especially to foreign journalists and the western media.

There is a brain drain taking place in Uzbekistan right now mostly because there are more economic and career opportunities abroad. When I was younger, I got the opportunity to study abroad through scholarships. Thanks to these scholarships, I have been to America and Europe but the situation in both locations directly influences what I will do with my future. For me, there is always hope that things will improve in Uzbekistan. When I graduate, I will have to make a decision. It is very easy for me to go back home, but bureaucracy makes it a bit of a hassle for me to get back outside. At present, in all of the ex-USSR states there are only two countries which require Exit Visas and these two countries are: Uzbekistan and Belarus. The last time I saw my family was two years ago, and the next time I expect to see them again is not sooner than a year, and not later than–who knows?

I’m somebody who was born in the USSR but grew up in an independent state (after the collapse in 1991). I experienced the transition first hand as well as the economic crisis and the rise of nationalism which followed. People usually talk about the importance of having a happy childhood, and for the majority of us living in that period our childhood was in fact quite happy, but it could have definitely been happier if our own parents were not struggling financially.

We had a scenario in which many highly qualified people (education was extremely widespread in the Soviet Union) had either no work or extremely low wages. We were also experiencing a huge shortage of basic supplies. Economically speaking, like in many other places in the Eastern Bloc it was a time of extreme struggle.

People found a way out of economic struggles through retail. Many people ended up smuggling goods–legal or illegal, mainly from Turkmenistan to Russia. People gave up their full-time jobs for these more lucrative opportunities, often leaving their family homes. The main business was textile and clothes, but illegal goods were being traded as well. I remember how drugs quickly entered the black market and became a big problem when I was growing up, starting from around the time that the USSR collapsed, maybe even a little earlier. The situation was exacerbated due to the conflicts that were already taking place in Afghanistan. Heroin, but more so a cheaper narcotic that they called “the black drug” (opium?) was very common within the upper middle classes, especially due to the geographic proximity of Afghanistan. The Soviet Afghanistan War began in 1979 and so did the mass production of drugs. It is nevertheless interesting how this was in fact a problem that mainly concerned the elites in Uzbekistan, maybe it is even the reason why it was considered a priority to tackle the problem by our government. The fact is that the average citizen or peasant couldn’t actually afford to take drugs.

In terms of drug smuggling and national security you could say we have made significant progress. I consider that to be an achievement since there’s been the Afghan War, where in fact most opiate drugs being sold in the market are being harvested today. Also, beginning in the early 90’s there has been a rise in the Islamic movement in Uzbekistan. Now clearly this subject has many dimensions as we have to consider that beforehand it was actually illegal to practice religion. People were thrilled to have this freedom back and it is quite interesting that despite almost 100 years of religious oppression, people still kept practicing their religions and traditional customs at home. But suddenly people were getting recruited to become Jihadists and fighters, and were getting involved in the Afghan conflict. Now, all of a sudden, people were even getting paid good money–enough to help the family to practice their religion–it seemed like a good window of opportunity, almost too good to be true! The fact is that the Islamic Movement grew rapidly after the collapse of the USSR, and with it extremism. In some of our country’s opposition I fear that I see a glimpse of this extremism as well. In any case, by now, it seems to me that this phenomenon of recruitment has also weakened somewhat, as many leaders died in battle in Afghanistan.

Some young soldiers returned, asked for pardon from the government and got reintegrated into society. But many others didn’t and had apparently succumbed to the extremist brainwashing. But the tightening of National Security also had a more imminent and simple motive–the general geopolitical situation in which my country found itself. We had wars taking place in the South–in Afghanistan, a Civil War in Tajikistan, and ethnic clashes in Northeastern Kyrgyzstan which are still ongoing. All these elements put together gave birth to the concept of a concentrated power and the idea that this type of power could potentially prevent destabilisation. Now, in these terms I can luckily say that there are no wars going on within our country today, and there have not been since we became an independent state.

The problems with tightened National Security? I don’t really know where to start. For many people, the elite have established themselves in our country and brought about inequality, as well as a central, monopolistic model of ownership (mass production of basic/export goods, the media, et cetera) Basically, we are talking about people who are in power and do not accept any type of criticism at all. Security does protect us, but it doesn’t allow us to express ourselves. I see it as a double-edged sword; security comes with a cost. We have been criticized internationally for the violation of human rights, but in my view it is not as if the International Community has offered us a feasible alternative. How can we feel secure, as a country, and at the same time liberalize politics in such a turmoil ridden region? If you look at the voices of the opposition, especially from abroad, it seems to me that if they took power today they would cause more problems than solutions.

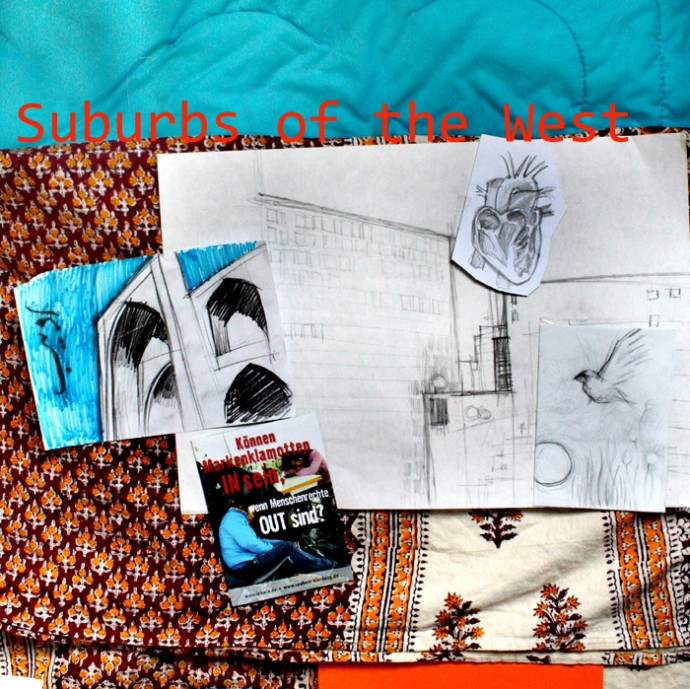

What my country’s government is mainly criticised for today is: 1.) Political Oppression, and 2.) Child Labor in the cotton fields. As for unfair treatment of dissidents and the like, I don’t have a personal experience I can recount. I do feel as though the West preaches a lot–but do you know where some Afghan Prisoners of War are questioned? They are brought to Uzbekistan, and are tortured here (by our regime or through the CIA/NATO extraordinary rendition program). There are registered accounts by Craig Murray– the former ambassador from the UK in Uzbekistan from 2002 to 2003–in which he voiced many complaints about the atrocities that he saw here, and for this he was immediately fired. In terms of child labor, I also add that I have yet to see Westerners rushing into change rooms of big clothing brand and other shops taking a pause to question the origins of the shirt or item they are about to buy.

Now, with the people I know, and in the places I’ve seen and lived in–you don’t really have dissidents. You simply have people trying to improve whatever situation they’re in within their given limitations. Of course, we can’t only talk about dark things. I would like to add that in my country, there are many great things like our exceptional hospitality, amazing dishes, and our strong cultural and historic identity which is present in our practices and architecture. I recommend anybody visiting Uzbekistan to get out of the capital, filled with its many Clubs and Westernized shops, and travel outside the city limits to distant regions. For me though, there is only one special thing, and it is my family.