If you thought nightmares on their own were horrifying enough, you may want to reconsider. Although it’s difficult to be precise about the total number of people suffering from it, sleep paralysis is a phenomenon many people will have encountered, whether it be frequently or occasionally. It is a temporary state of feeling paralysed upon falling asleep or waking up that is often accompanied by vivid hallucinations that are usually very frightening. Fattana Mirzada, a Criminal Justice and Psychology student originally from Afghanistan but who has spent the majority of her life in the Netherlands, shares her experiences with sleep paralysis and the cultural clashes she came across while trying to make sense of what was happening.

I was 15 when I first experienced something that was very similar to an episode of sleep paralysis halfway through a nightmare. In it, I was in my bedroom and a Grim Reaper figure was going through our hallway, closing the doors to the bedrooms of all my family members one by one. When he had closed the last one, he turned around and stood in front of my door. I was terrified and all of a sudden I felt my body paralyse and was overcome by a feeling of being awake but I couldn’t seem to wake up. It was very weird because when I finally did wake up, I couldn’t figure out whether what I had dreamed was real or not but soon shook it off and didn’t pay much attention to it at the time.

A year later, I experienced another episode of sleep paralysis which was much more intense. It was another nightmare in which, as silly as it sounds, I was being chased by midgets who I thought were demons. I ran and locked myself in my room only to be faced by my French teacher who had appeared in front of my window. She was very thin with short hair and I realized that she was a demon, too. She managed to climb through my window and came closer and closer to me. I started chanting a verse from the Quran over and over again to comfort myself. When I got to the end of the verse, I woke up.

I told myself it was a dream and laughed at the fact that my French teacher, who in real life I thought fondly of, had taken on the form of a demon in it. I went back to sleep again and at that same moment, I started to hear shuffling. I brushed it off, assuming the noise was due to my brothers playing football in their bedroom upstairs. As I continued falling asleep however, it became louder and louder and the sound came from right above my head. The moment it ceased, I instantaneously felt as though my entire soul and body dropped through the bed, only leaving behind my skeleton. I realised I was paralysed and unable to wake up.

At the same time, I heard a little girl somewhere above my bed singing, much like in one of those horror movies where you know the outcome will be anything but good. I was incredibly frightened. I could even “feel” her hands hovering above my head, just brushing my hair. The state of being paralysed, confused, unable to wake up, and simultaneously be trapped in a nightmare – you can’t imagine how extremely frightening that is. Far away I could feel my hand resting on my leg and I tried pinching myself in an attempt to wake myself up. Eventually I felt myself gain control over my body again. The whole episode seemed to last for hours but when I finally woke up, the episode probably only lasted five to ten seconds. I ran to my mother and recounted my dream to her. She was shocked because she didn’t understand what was going on. She tried to convince me it was just a dream, but I told her, “No! I was awake! I was fully awake when it happened!”

That’s exactly what’s so frightening about sleep paralysis. You feel awake, but at the same time you’re stuck in transitory state between sleep and wakefulness so everything in your dream feels very real. If you’re having a nightmare, you still have the vague notion that you’re dreaming, but when you’re suffering from a sleep paralysis episode, you’re basically hallucinating. Because you feel you’re awake and in the real world and not in your dream world, everything feels real. You can see it, you can feel it, and you can hear it. So whatever is happening must be real because you’re awake and you can still reason. The hallucinations are often terrifying and they can be visual, auditory, tactile, and some people also have olfactory hallucinations.

Because it all feels so real, sleep paralysis episodes are much more traumatizing than nightmares. You could compare it to watching a violent movie. It may not affect you much, but if you were to experience it in real life, it would be much more traumatizing. On top of all that, sleep paralysis also carries the fact that you’re paralysed and unable to escape the state you’re in. You’re fully aware of your body, but can’t move or respond. Some people also have out-of-body experiences during sleep paralysis, but I’ve never had that happen to me.

My mother’s explanation for what had happened stems from my Afghan background. Sleep paralysis is a fairly famous phenomenon in Afghan culture where the term for it is sayeh pakhtsch, literally meaning ‘suppressing shadow’. The story behind the term is that the benign suppressing shadow wakes you from your sleep so that you can pray or because you didn’t pray the night before. Seeing as I had woken up my mother at four in the morning, she said I had probably been roused by the sayeh pakhtsch for my morning prayer. Nevertheless, I found it difficult to accept this explanation because I could not see why it had to wake me up in such a horrible and terrifying manner. To me, a biological explanation would also seem necessary because it was such a tormenting experience.

I had tried to analyse what was causing my episodes but my daily activities didn’t seem to coincide with the episodes and they just seemed to occur randomly. Now I know that sleep paralysis peaks from age 16 to 25 and that it tends to occur most often to those in puberty, so that could have maybe set it off. But during the time I experienced sleep paralysis on a frequent basis for almost a year, I was also suffering from headaches and I thought that perhaps the two were linked. I went to visit my GP and told him about my headaches and about the terrifying moments in my sleep when I was paralysed. I didn’t tell him that I hallucinated during the sleep paralysis, but I mentioned that I heard voices and saw things. He gave me the impression that he knew what I was talking about and simply told me it was nothing and not to worry about it.

I decided to follow his advice and just see the sleep paralysis episodes as unusual bad dreams, but when I went to university and started researching it, I realized many more people experience sleep paralysis. Those who visit their GP often hear the same as I was told and although my sleep paralysis didn’t affect me severely, some people do suffer a lot and develop anxiety disorders, depression, and other maladies because of it which can have a very negative impact on their daily life and functioning. For my social psychology course, we had to develop a flyer and I chose to do it on sleep paralysis. When discussing it with my class, three other students also shared their very similar experiences.

None of them had ever been able to identify what they were experiencing because when you look up your symptoms online, most of the results are mythical approaches to dream analysis and stories about other people’s dreams. The terminology related to sleep paralysis can be quite scientific and vague and therefore bar people from knowledge and understanding. I took my flyer to my GP and told him about it. He was surprised and told me he had never heard of it. The other physicians I visited expressed the same.

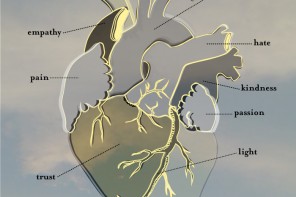

I think that this reflects the lack of knowledge the general public has when it comes to sleep paralysis. Many people who experience it hesitate to share their experiences with others because most people don’t understand. You already feel as though you’re crazy and somehow disturbed, and confessing your experiences to others often leads to people thinking the same thing and recommending you to visit a doctor. In the Western world, I think there is quite a lot of stigma attached to these kinds of things, but in many other areas of the world, the approach people take to these phenomena is more spiritual. In Afghan culture, people will tell you that it’s the work of God.

But it’s not only Afghan culture. African, Japanese, Indian, Chinese, etc. cultures acknowledged sleep paralysis way before it was addressed in Europe in the 1800s. This difference in perspective also reflects how people treat sleep paralysis. Doctors in Europe might give you medication for it, but in Afghan culture, you’ll be told to just deal with it and it’s not regarded as anything special. I personally prefer a more scientific approach over a spiritual one because I find it much more traumatic to actually think that the demons in my dreams are real and that they can hurt me anytime they want, especially when I have episodes on a regular basis. I wouldn’t ever be safe on my own, even in my own bedroom. Thinking of sleep paralysis in scientific terms comforts me because then I regard everything as a dream.

After doing a lot of research on sleep paralysis, I’ve found a way to prevent myself from having an episode. Due to my psychology and neuroscience courses, I had access to a lot of reliable research and no longer had to rely on websites with random explanations purely based on spirituality with no evidence to back them up. Finding scientific explanations was reassuring because you see that what you’re experiencing is an actual phenomenon and that there is evidence-based research to support its occurrence. I found out that by moving the small muscles in my hands and feet, it takes much longer for an episode to occur, if at all. If I do happen to fall into another episode, I keep trying to obtain power back over my body because when you just let it happen, the episodes seem to last longer. For some people, reducing stress or changing the position in which they sleep does the trick.

Lately, I haven’t experienced sleep paralysis as often as I used to. This is probably because I have become much better at preventing the episodes from happening. The full process of sleep paralysis is still not fully understood but I plan to continue my research on sleep paralysis when I start my masters degree in Clinical Neuropsychology. It can be difficult to unite the worlds of spirituality and science when their views are so contradictory to one another, but I hope that with my knowledge and background of both, I’ll be able to make them more compatible or at least create some understanding between the two.