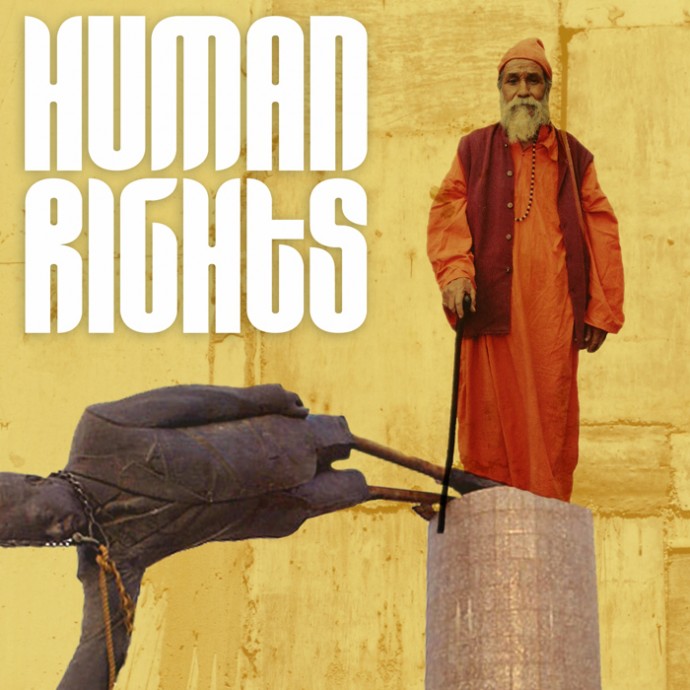

Why Human Rights Really Do Matter

You hear human rights here, human rights there, human rights anywhere you go. We hear and read human rights so much that most of us forget what it is all about or if it is still worth talking about. Emanuel Stoakes, journalist and human rights activist, sheds some light on the topic. In a world of shifting power, economic struggle and laws changing day by day, he discusses what the term human rights mean today and what it has to offer to the future.

While enjoying drinks and conversation, I got challenged by a friend of a friend about the worthiness of my concern about human rights. Even though it was not the first time I heard such claims, I found myself astonished. I proceeded by explaining that he should therefore agree with the following set of events –I come over to his house in the middle of the night with a gang of armed men. I take my time to torture him, and if I feel like expanding the fun, kidnapping him for an indefinite period of time. What would the consequence of such an action be? Nothing, I am to be protected under law because I’m close the attorney general. I end the anecdote by asking if that appeals to him.

I have done this to more than one person and nobody ever responds with a “Yes” and means it.

I concede that the above may be an extreme and slightly weird thing for me to say, but it raises meaningful points. If we want to be free from unimaginable abuse and injustice ourselves, then we surely have to accept that all human beings should be free from it. The universalist principle, something that is routinely unheeded or intellectually effaced by dictators, great powers and their apologists is placed immovably at the heart of human rights. It rejects the antiquated and ever-false notion that some people are superior, that arbitrary characteristics such as birth, ethnicity, gender or social position can determine one’s access to the protections that others enjoy. The central text of the rights movement, the Universal Declaration of 1948 asserts that certain fundamental birth-rights are granted to all global citizens, without distinction. This was adopted by the UN general assembly on the 10 December 1948. The principles it contains were timely and momentous: they prefigured the end of American segregation, the break-up of apartheid and the final collapse of European colonialism. The Declaration and, moreover, the values it upholds are a triumphant landmark in the modern era, the world that we inhabit now with laws and protections we take for granted. Its span covers all the essential human requirements for life and dignity ranging from freedom from slavery to the right to food.

The declaration also calls for “an international order in which human rights can be fully realized ”- something that, to this writer at least, sadly remains an aspiration for the global community, the world being as it is.

Having said that, the importance of the Declaration to the UN charter and customary international law means that human rights are largely protected under legally binding arrangements. The emergence of modern International Humanitarian Law from its legacy assisted this, as did the Geneva Conventions. Despite the fact that various countries have mocked, infringed, flouted or egregiously pissed all over international law in the years since the Declaration was announced, many of the world’s oppressed people can now turn to its provisions in their case for justice.

But enough with the past. I really think the great beating heart of human rights is its affirmation of humanity, its ability to transcend normally incommensurable differences without alienating anyone. This may be because the principles upheld by human rights are free from the exclusionary prescriptions, metanarratives and/or dictations of any singular cultural or creedal belief. Yet its core values are drawn from the common cultural treasury of our species: in it we see echoes of the Ubuntu philosophy from Africa, the ancient Manu Smriti traditions from ancient India, the central teachings of the Abrahamic religions and the liberal humanist ideals of the European Enlightenment. Thus, the human rights outlook encompasses a remarkably flexible, inclusive “consensus narrative”. Because of this, people of humane impulse from all backgrounds have joined the movement.

There’s plenty of ground to be made. The human rights project is a work in progress. If we just look at recent years, incidents that occurred during the Global War on Terror, the Sudanese and Sri Lankan civil wars, even the treatment of Bradley Manning by the US amount to serious alleged human rights abuses. Instead of a world in which these sorts of things are allowed to happen without any come-back, we can all thank the HR community for having created ways for the powerful to be held to account. Recently, Charles Taylor, the former President of Liberia was sentenced, effectively for the rest of his natural life, for his part in what presiding Judge Richard Lussick described as ” some of the most heinous and brutal crimes recorded in human history.” That’s no small victory for justice. Several of the big players in the Bosnian genocide have now also been caught and had their day in the dock.

Yet so many injustices endure, and rights laws are applied inconsistently around the world. Dictators die without facing their crimes. Others, having won advantage for a nation’s elite, receive domestic reward for their “achievements” at the cost of humanity and live comfortable lives. So far, the International Criminal Court has focused overwhelmingly on hosting cases against Africans. Some, like legal expert Chris Mahony, have argued that, in the international justice system “the world’s great powers… decide who is prosecuted, and who is not.” This desperately needs to change- yet these are the flaws of the international system, of governments- not the human rights movement.

In a world where the likely future ravages of climate change will bring about unprecedented new challenges, where ineffable market forces may once again wreak bitter havoc in the lives of the inculpable, travailing ninety-nine per cent, human rights are only going to matter more and more.

For this reason, it is in all our interests to care about this under-appreciated cause. I can finish my drink my point is made.