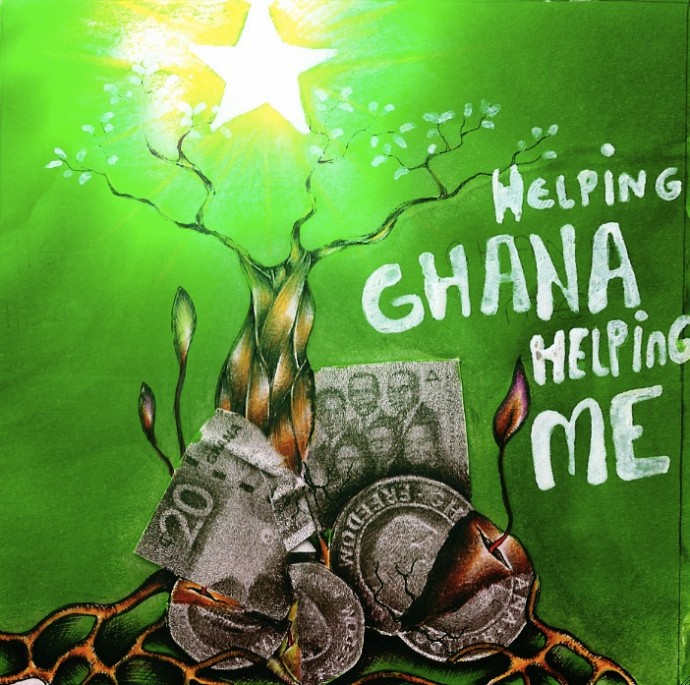

We talked to Ines, a student of ecology, who volunteered in Ghana last summer. She taught children of two villages, Azani and Butre, about taking care of environmental issues. She says she applied for the volunteer position because she thought Ghana needed her, but it turned out, Ghana was everything she needed instead.

There was this boy from my village in Ghana, Emmanuel. First time I saw him, I was walking home, deep in my thoughts, when I heard a sudden “Hello, hello!” Then this boy appeared out of nowhere, jumped straight into my arms, gave me the biggest hug, and then disappeared just as quickly as he came. He did that every time he saw me walking towards the village. After a while, I got so used to it, I found myself desperately wishing to hear his “Hello” as I slowly approached the library I lived in, making sure my arms were free to receive his hug. A big hug for the end of the day; that’s all he ever needed from me. And to be honest, it is all I ever needed from him. We probably only exchanged a handful of words during my three month stay, but nevertheless, he is still one of my favorite people I’ve met there. To me, he’s a definition of happiness.

Was that the kind of person I thought I’d meet when I decided to volunteer in Ghana?

I went to Ghana to help. I wanted to make a difference, to have an impact, to change the community. I honestly thought that I, as an educated ecologist, could offer them a perspective and knowledge they need in order to improve their lives. That is why people head for Africa, isn’t it? We want to help, but mostly we believe they need us to help.

I am not proud to say my image of Africa used to be not that much unlike Kevin Carter’s famous photograph of a vulture preying upon a child. All the stereotypes in the movies, the images circling the web and the media discourse had me thinking Africa is a poor country of poor people that need our help. It’s not like I expected that everyone would be starving and on the edge of life, but I definitely thou

ght there would be some severe problems, especially regarding some basic human needs. I believed that poverty is a factor that affects every aspect of their lives; that the quality of living is neither what it should be nor what it could be. And of course, that I could have an impact in improving their lifestyle.

But once you are there, you realize you had it all wrong. It is true that Ghana’s state system is not like Europe’s: the health care system is problematic to the point where people won’t go to the doctor because they don’t want to be a financial burden for their family. Ecological awareness is practically non-existent. Ghana doesn’t have municipal services, so problems with environmental pollution aren’t a surprise. The lack of cleaning devices and insufficient knowledge of waste and wastewater management all suggest that there is still much to be done in this direction. Ghana as a country has its issues, no doubt. But, ultimately, the state is one side of Ghana; people are the other.

Ghana’s people don’t have much from a European point of view. But through the eyes of a European that has spent three months with them, they have it all. I’d say it’s the sense of community – the bond that people share – that makes all the difference. Ghanaians feel safe in their environment, because they share such a strong connection with the people around them as well as with the area they live in. It is hard to describe their utter content with life, but you can sense it in their smiles, in their gestures, in their words. “You can never go wrong with a smile”, a friend once told me. I know it sounds patronizing to say, but I see them all as children – so genuinely satisfied, so happy with what they have, and especially with whom they have around them.

Luckily for me, that attitude towards life was contagious. In Ghana, I was the happiest I’ve ever been. I felt the kind of inner satisfaction I never knew existed. As if anything could go wrong and it wouldn’t matter. As if I could cope with things that would’ve crushed me had I not been there, in Ghana, amongst those beautiful people.

When I decided to go to Ghana, I never realized that I, myself, would gain so much from my volunteer experience. Sure, you never sign up for such an experience for entirely altruistic reasons. You always expect there to be something beneficial in it for you, too: I believed that I would perhaps gain some working experiences, maybe some connections and references; that I would grow as a professional. I did do that, but also – as cliché as it is – I grew as a person. That might even be an understatement; I think I have actually become a different person. I changed my perspective of the world and reconsidered both my priorities and my life goals. I have changed to such an extent I have failed to reconnect with some friends upon my arrival back home.

I soon realized they have given me so much more than I could ever give them. There I was, in Ghana, expecting to be the teacher, but, instead, becoming the student. I felt kind of naive in my anticipation to help them, to teach them, to be—I can say it now—the one in control. I never expected it to be an entirely unilateral process of me lecturing and them learning, but I did think I would be the one who would do most of the giving. But, being there, I couldn’t and wouldn’t step into the shoes of only their teacher, and thankfully I didn’t; otherwise, I never would’ve bonded with my children—a highpoint of the trip—the way I did: Their smiles, their laughter and their warmth soon became my drug, they kept me going when I was too exhausted to stand up, and the memory of them keeps me going even now.

The fact that they—the children, the people, the community—had such a bigger influence on me than I had on them, has made me feel almost selfish. I started questioning my motives, my every decision, my every step. Without wanting to, I took so much more from them than I ever could’ve offered. I feel like I owe them, although I suspect there is no such thing as a debt in Ghana. I was helpless in my knowing that I could never repay them for what they’ve done for me. For me, it was a life changing experience, but was it for them?

I started to ask myself do we really do them any good with our intended help? As you realize that Africa doesn’t really need the help the European media claim they do, it becomes clear that your volunteer work won’t save any lives. You probably can’t change them either. I do hope the children I taught still remember what we worked on in class and that they still practice what I preached, but I realize it is a small hope at best. Maybe some of them still remember me at times, and instead of throwing their rubbish straight on the shore, they throw it into the trashcan. Most likely my students are doing as others do, and not the other way around.

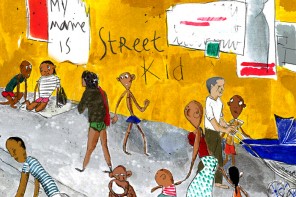

It’s not like our presence doesn’t affect them; it does. But not necessarily in a good way. The constant presence of white people, volunteers as well as tourists, in Africa has imposed a certain value system that hasn’t been there before. Like the importance of money. Even though most Ghanaians have enough finances to get by, they have embodied an ongoing dream of succeeding, of living a better life, a ‘white’s life’. And since they see white skin as a symbol of success, foreigners are usually greeted with: “Obroni, 50 pesewas, please!” It’s an unpleasant feeling, to say the least. You feel shocked and half-ashamed that all you represent to them is the color of your skin. When my co-volunteer finally broke down in tears, and the children were forbidden to ask for money, the words were left unsaid, but the feeling wouldn’t go away. That is until some weeks later, when we established a reward system in the classroom, based on the awards in the form of “Earthpoints” for every environment friendly good deed they did. Then they forgot all about the pesewas, and started to demand I give them Earthpoints instead. And there it was, my small victory.

I cannot tell you how many times I’ve heard that word, “obroni”, or “whitey”, during my stay in Ghana. Probably every time I’ve encountered someone I didn’t know before. It sounded a lot like “outsider” to me. But after some time, I learned a word I could counter them with—“obibini”. It was like this word was a deal-breaker: By saying it, I was no longer a rich tourist. I became “their obroni”; white, yet familiar face. I think it was then when they started to recognize me for the person I am and not only for the color of my skin. That is when you as a person start to matter, and maybe, when even your words and your lectures become more significant as well.

I left Ghana with such mixed emotions it took me several months to set them back in order. Coming home was even harder than leaving it three months before, and settling back in my previous life was a bigger culture shock than arriving in Ghana in the first place. Even though I have found my place at home once more, I intend to go back as soon as possible. I will do everything in my power to repay them for what they gave to me, for what they’ve been for me. This time, even though I will still do my best to help, I will go with a completely different image of Africa and its people in my mind. I know what will wait for me down there—another world, a better world.