The human need to leave marks on our surroundings came to light about 40,000 years ago when Homo sapiens started painting and carving pictures in caves and on rocks. Since then it has been evolving and transforming and presumably it will continue to do so until the end of the time. Today, the closest form to what our ancestors did is called graffiti, and although it has become mainstream, to the public, it is taboo. Society calls graffiti artist vandals, but they call each other kings.

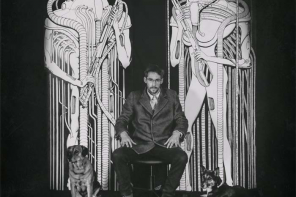

John Zwenka has been a vandal since he was a kid. He is a walking shadow while you sleep, and whether you like it or not, he is secretly adding colour to your grey city. Surprisingly mild and at times altruistic, this art form is often misunderstood. John reveals his idea of the ‘spirit of graffiti’ and shows how street art can take on a very different meaning than we might imagine.

I was born in a little village in East Germany. I remember being trouble in kindergarten, beating up ugly kids and stealing their lunches. My mother was freaking out, so I started doing sports to calm her down. At the age of six, I started painting. My father used to draw a lot, and he taught me some basics. I thought that it was cool and I wanted to make it more explicit. At the age of twelve, a small graffiti shop was opened in my village. I suggested to my friends that we should go buy some spray cans and try to paint with them. And that was the beginning of my ‘graffiti career’.

I realised that spray paint is an amazing medium to paint with. You can apply it on any kind of surface and the colour dries so fast that it gives you the impression the piece will last forever. Often, we stole our cans from tool shops, since we couldn’t afford them, and our parents were always suspicious about our lunch money going so fast. After experimenting with spray paint, we founded our first graffiti gang. We started painting our hometown to such a degree that police started searching for us. Most of us were lucky and fast enough not to get caught.

After a certain point, people started asking me to paint their walls for money. Although the cash was appealing, back then it wasn’t cool to paint for money. It would be bad publicity for our ‘brutal’ graffiti gang. You see, we were also trying to be the tough guys—at most, we were doing it for spray cans or free beers.

When I was thirteen, my parents got divorced. I quit doing sports and started smoking weed. I was already pretty confident, and my mom was trying to do me favours to cover the loss of my father figure, so obviously, I took advantage of this. I used my situation as an opportunity to get into bullshit. Nothing really mattered to me back then. I was hiding my hobby well and could still show her my legal pieces, which was making her happy and proud. My father was an artist, and so teased me a bit about my ‘art’, but since I didn’t beat people up or steal things he was fine with what I was doing.

As I got older, I needed money for weed, more spray cans, and to spend on girls and alcohol; therefore, between the ages of fifteen and sixteen I also started painting legally on ‘halls of fame’, walls that were specially sanctioned by the city to be painted on, and even portraits of fat grandmas. That felt great, but going out with my friends to paint trains was what made me feel free. That was a completely different feeling and a much stronger experience. We only had a few minutes to make something really cool or really ugly. Having that limited time to bomb a hot spot on the street or a train yard was always exciting. My hometown borders Poland and the police station is directly next to the train yard, so it was quite risky but so much fun.

Once, I went on holiday to the mountains of the Czech Republic. One night, I was walking alone in the middle of nowhere, when suddenly I saw a piece that a friend from my hometown had painted. I got goosebumps and stopped for a few moments. This is actually the ghost and spirit of graffiti. The effect it has on someone else even long after it’s created. The feeling conveyed was, “I was here”. It makes you feel a sense of eternity and the piece seems like it will stay there forever.

In 2005, I moved to Berlin. I started joining meetings at the halls of fame to get the feeling of the graffiti scene and I was constantly checking out hot spots to hit. Berlin, in my mind, was always the city for art and graffiti, so when I arrived my motivation was increased. Gradually, it became impossible to walk through the streets and not see graffiti. It was everywhere. Looking at all the fresh pieces on the walls always made me think, “Someone had the balls to paint last night”.

The high quality of the graffiti pushed me and my friends to improve. We started hanging out with other artists and creative people. A few times we got in trouble, but nothing really extreme. It was really just about which crew would conquer the train yard in the end. After screaming and trying to convince the other crews that the yard belonged to us on a particular night, we would eventually end up talking, discussing, sharing the trains, and becoming friends. At the moment, I consider most of the East Berlin graffiti crews to be my family. We are a huge group of different and various crews, styles and artists. It is always good to be in touch with the newest ideas and styles.

I don’t like talking so much about graffiti though. I like talking with it. I know that it’s my graffiti that stands out there, speaking to people—or not. When I meet people, I try not to mention graffiti at all. In the end it’s not important in a face-to-face conversation. I find it ridiculous when guys introduce themselves with their graffiti name, or when random people ask me about my pieces. Graffiti has nothing to do with talking—it’s just acting. Graffiti is an uncensored medium, so that is the conversation. You paint something, people see it, and either they react or they don’t.

Graffiti is our way of rebellion. Through this, we switch off the play button of our daily routine. Every moment of painting is a small mission in itself. The feeling differs from time to time. Sometimes it’s fear and stress, but mostly it’s like having butterflies in your stomach. If I like a piece I’ve made the previous night, my whole day is going to be good; come what may, my mood is fixed.

Then the fame feeling comes—in fact, it’s always there. You’re walking in your district, which is always the area you’ve painted the most, and you feel like a king. Certainly that makes you feel more safe and at home.

With or without these satisfactions, graffiti is a pure addiction. First of all, I never feel that I’ve painted the best piece I could, and therefore I’m always searching for the perfect one. I really hope that it will never come, because when it does it will be time for me to retire. Secondly, I have this impulse to keep myself in the scene, to stay active. To be honest, it makes me feel alive. I can’t imagine myself as ‘normal’ guy. Who can even define what’s normal nowadays? But I hate the idea of having an ordinary routine: waking up, going to work, returning home, fucking my girlfriend, preparing dinner, watching TV and going to bed.

I definitely need variety, and every single graffiti action is a new adventure. You can’t predict how it will evolve, or what will follow. It’s totally fun. You just need to keep in mind that you have another life too. Loads of the people I know with big names in the graffiti scene turned thirty with no cash and no interest in life without graffiti. That’s not where I want to be. Being born and raised in Germany requires a constant discussion around the future, money and the proper ‘ideal’ job. For me, it’s the balance you have to achieve in life. But what about the factor of art? Even though I’ve been sketching and drawing for nearly twenty years, it’s just in the past five years that I consider what I’m doing as art. When you find your way, and find the thing that keeps you passionate about life, that’s the thing you have to follow. When you love something it’s fairly stupid to quit.

Today I am twenty-seven years old and I have my own graphic and web design company. This is a big challenge, as it means my painting gets far more complicated and demanding. Sometimes, it takes days for the perfect idea to be born and sketch it out. The challenge keeps it interesting; still though, illegal graffiti is a need for me, and I do it at least once a week. Then my life is balanced. Beyond the canvases I make, the painting orders, and the good vibes I receive after I’ve finished these products, nothing can replace my passion for graffiti. The future I’m dreaming of consists of travelling, creativity, people, exhibitions in New York City, and at the end of the day going out to bomb a wall, no matter what. All I want is to keep myself in the graffiti scene, combining my illegal passion with my legal art.

Graffiti was born on the streets. Its freedom and magic can only happen on the streets. Being outside, and painting something you like, creates a feeling that can’t be replaced. It goes on and on, like a vibrant, breathing being, and nothing can stop it. The major intention in art is to create something significant that might stay alive even after you’re dead. Sometimes, even one thing is enough to keep you in the future consciousness. This, to me, is the most beautiful thing, to create something that can influence humans in the future, in good or bad ways—it doesn’t really matter. The point is to add something into the daily routine and people’s perception, to make them think further. It’s important though to create an individual product. It’s about storytelling, sharing and receiving individual experiences and thoughts through the freedom of art.

Society makes a huge effort to fit all of us in boxes and put us to bed where we dream no dreams. Illegal graffiti is our attempt to show our fight against living under society’s control. Even though we are manipulated daily in different ways, we have the right to say, “No. This moment is mine, and no one can take it away from me”.

Today, many people are so deeply imprisoned in their miseries and problems, that they completely forget about the bigger things. To me it’s greatly satisfying to read any kind of sentence I see painted on a wall while I’m out walking; it puts a smile on my face. For a moment, anything that stands out there on the streets and suggests that I should think a bit makes me instantly feel happy, and makes me remember I’m still alive. Sometimes I think that the art itself is maybe not that important, but more that it has the power to create a great impression on people. This is crucial in order to escape monotony and experience the reality you choose for yourself. And the more open-minded you stay, the more people will join. In the end, it’s all about really living and doing what you love.