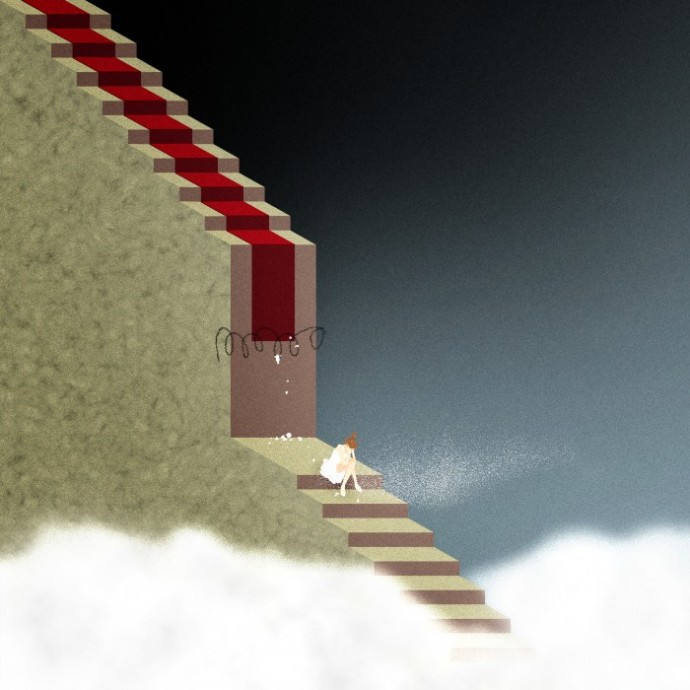

A dream. A thought, an image, a wish – that given the time and attention, can snowball into reality. It cannot truly be forgotten, nor replaced. Starting as inspiration it can ceaselessly motivate you, and before long it can even control you, and dominate not only your life choices but also your inner being. Dreams have the power to shape reality, to drive human beings to incredible lengths, and to separate the determined from the indecisive. But there’s something funny about dreams: they hold the weight of someone’s world in their gossamer wings. If a dream does not come to fruition, what happens to it? Like the light in a room that has been turned off, is it extinguished? And what of the dreamer from whose mind it came? Sensa Nostra speaks to ballerina Jenna Carroll about her experiences in the world of dance and about what one can truly learn, lose, or gain from setting your heart on something.

I have been dancing for over eighteen years now. Originally it was one of those after-school activities you pride yourself on as a kid, and then, just like anything you set your heart on, it grew. Ballet was my first choice and my first love, but every dancer knows that versatility is key in the dancing world, and so with age I began incorporating other styles such as contemporary, jazz, musical theatre and tap. Each was, in its own unique way, beautiful; however, Ballet had stolen my heart when I was only four years old and taken a grip so powerful there wasn’t much that could even flirt with the bonds that connected us.

Through time, dance began to define me as a person. I had lived and breathed it for almost all of my life. In fact, ever since my childhood amnesia passed and my memories started being built, I had already begun dance classes. It’s difficult for many people to grasp, but I viewed my connection with dance more as a relationship – something sacred between the music, the movement and myself. So powerful this bond was, that rather than a choice to participate it felt more like a natural progression for me. I distinctly remember telling my father when I was nine years old that when I grew up I was going to go to England and dance professionally. There wasn’t a shadow of doubt in my mind – I was going to be a real-life ballerina. And I did. From that point on, it was all so very clear to me – my passion, my dream and the path I’d take to get there.

I have no singular recollection of ballet ever being a hobby in my eyes. I was always very serious, even as a child – being earnest was one of my most powerful attributes. Simply put, I just wanted to be the best, and my competitive streak was vital in my pursuit to become a professional dancer. I remember my teachers telling me that ballet was ‘my thing’; it pushed me beyond belief hearing that. Consequently, whilst other children ran circles in playgrounds and swam at the beach, I trained repetitively around the clock, striving for unattainable perfection.

Ballet has always been my first choice of dance for numerous reasons. Firstly, the tradition is immensely intriguing. The history and movements are so conservative and have, over hundreds of years, kept a firm hold of their dignity and not strayed due to the changes in society. Of course this could be debated, but in my eyes the poise and elegance that embodies Ballet is still as relevant today as it was hundreds of years ago. Secondly, the aesthetics captivated me from the very beginning; the graceful and sophisticated nature of the movements, in my eyes, was nothing less than pure beauty. The challenge is another aspect that fuelled my motivation. Considered the highest form of dance, the flexibility, strength and agility behind the movements is one thing – making it look graceful, light and effortless is another.

To reach your dreams in the ballet sphere, altering your life is imperative. However looking back, it never felt as though I was sacrificing anything because my love for dancing trumped my desire to lead an ordinary teenage life. I didn’t finish high school, I gladly spent my weekends competing or rehearsing, and I in turn didn’t immerse myself in the party life or hang out with boyfriends like most normal girls would. My dream required more than just time – it demanded a fixed lifestyle – and now I often find myself wondering if I missed out on certain milestones. It never really felt like a choice; it was as if it was expected of you. If you wanted to pursue this career you knew the path you had to take from the beginning.

Adolescence is one of the many demons that haunts ballet dancers. Going through puberty in a leotard and tights in a room full of mirrors is difficult to say the least. Learning how to dance with a new body feels almost like starting again. Ballet dancers are conditioned to favour a different ideal body image. We don’t want bums, boobs or hips, or anything that slightly resembles a feminine body for that matter. It’s an endless circle of disappointment until you learn to accept it, which I still haven’t completely mastered.

My body was something that worked in my favour until my breasts made an unwelcome appearance. This raised my anxiety levels through the roof and I changed my eating habits in the hope that I could prevent gaining weight. This in turn led to a lack of energy and malnutrition. Shortly after, I ended up fracturing both tibiae because my bone density was so poor. Injuries were another challenge: every dancers worst nightmare. You see everyone else improving, whilst you are stuck on the sidelines, so to say. And in an industry so competitive, you simply won’t be used for productions if you’re not reliable and strong.

Moving to England at the ripe age of 16 was one of the most difficult challenges I have faced. Leaving behind family, friends and the Australian sunshine for a lonely life in rainy London was painful, but like everything else, it wasn’t seen as a sacrifice – it was expected. My training was demanding and exhausting, but the most arduous part for me was never seeing the sunlight. I would walk to ballet before the sun rose and arrive home under the stars. I would be indoors all day, which was such a stark contrast to my upbringing on the beaches.

Nonetheless, there were also incredible days, after which I could not have been prouder of myself. So rarely do you come off stage satisfied with your performance, that when it happens it truly is something exceptional. A performance I did in London; I’ll never forget the feeling. I had selected a solo piece and deliberately picked the hardest one on the list of repertoires. I trained until I knew every step like the back of my hand, but even then I was high strung as to how it would unfold under pressure on stage. Be that as it may, when I stepped onto the stage for that competition everything flowed perfectly. I was also privileged enough to dance alongside my childhood idol, Tamara Rojo, in Japan, for a ballet production of Sleeping Beauty.

Looking back, I did accomplish many of the goals I set out to. However, my dreams were forever growing, so I never felt as though I really got there in the end. I’ve found that sometimes in life you get to where you thought you wanted to be and then realise it doesn’t fit with you as a person. It really is heart wrenching to let go of such a powerful part of you. It’s like a breakup in a sense, but you can’t console yourself with the thought that ‘it wasn’t meant to be’ after you have dedicated your life to it. Ballet demands your whole self – you physically and emotionally have to hand yourself over to ballet.

Above everything, the greatest lesson I have learnt from my failures and success in the ballet world is that everything changes. Psychologically our brains mature with age and in turn we see the world under different lights. As a child, I was focused. My hormones weren’t yet on the scene and physically I accomplished a lot, as my body was undamaged and resilient. In saying that, I now acknowledge that the dream I let govern my life choices was the dream of a younger version of me. Nine-year-old Jenna. With ballet, it’s almost as if you’re living in some kind of a fairytale world. You remain physically and mentally immature to stand intently alongside your dream. Of course you are challenged, but you don’t face the everyday ‘normal challenges’ that go hand in hand with adolescence. If you don’t watch out and reassess your desires often, you could end up thirty with a nine-year-old frame of mind and a tonne of regrets. You need to learn to be honest with yourself and not let your dream cloud your judgement beyond repair. When all is said and done, life goes on, and your dreams should develop with you.