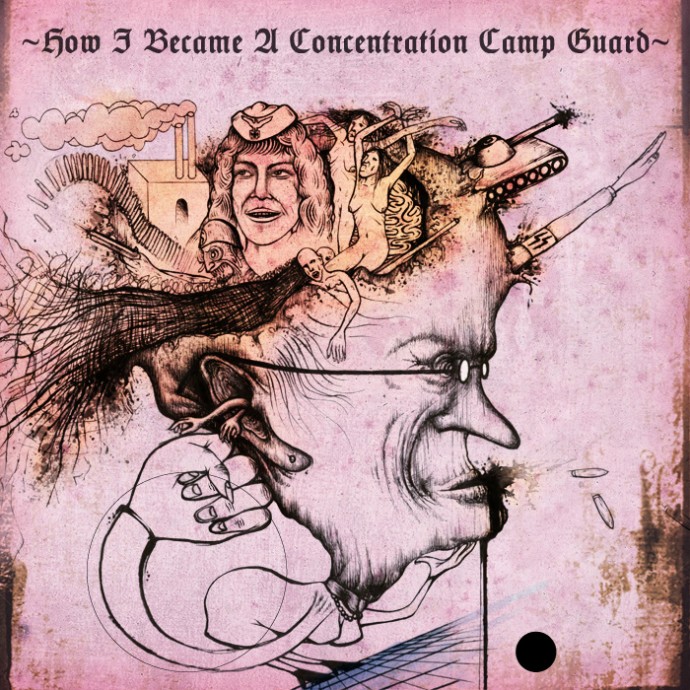

We have all heard about Auschwitz, Dachau, Treblinka, and the atrocities that were committed there about seventy years ago. From the twelve thousand camps and sub-camps established between 1933 and 1945 — an estimation from the German Ministry of Justice — only a few names stay in our memories. Yet all the camps are still haunted by the ghosts of their pasts. Among these is Ravensbrück, a concentration camp dedicated to the imprisonment and extermination of women, which employed roughly one hundred and fifty female SS guards. Were they National Socialism fanatics, sadists, or sufferers of mental illness? No, the vast majority of them were normal people like you and me. Margarete, 91, a completely ordinary woman, worked in Ravensbrück for nine months. Here she explains to Sensa Nostra how she unwittingly took a job supervising prisoners at a concentration camp.

I waited for many years for the Berlin Wall to fall before coming back to Ravensbrück concentration camp. I felt that I needed to. The district of Mecklenburg, with its red-tiled houses, is beautiful. The quiet calm of the area contrasts with the actions that have been committed there. Many barracks of the camp were destroyed, and the factories that once served the war are entombed, but I am still able to recognize the place. And I have the will to narrate my story, to help.

In August 1944, when I was twenty-one years old, I was working as a lab assistant filling bombs for the Luftwaffe at Ruhrchemie, a chemical company near the western border of Germany. My best friend told me she had signed up for an apprenticeship outside Berlin, for which I also decided to apply. We did not know exactly what the job consisted of. A few days later, we took the train eastward through the Ruhr Valley, which the Allies had bombed and destroyed. When we got off the train, the barbed wire and the surroundings led us to assume we would be working in a concentration camp. The assumption was confirmed when we saw the prisoners through the window of the SS cafeteria. We were furious. We had been employed as the women’s auxiliary of the SS to be guards, or more accurately, to be Aufseherinnen (supervisors).

Ravensbrück concentration camp, located fifty miles north of Berlin, was built in 1939 and imprisoned one hundred and thirty thousand women in total, of which 84% were political detainees (communists, resistants), 13% ‘antisocials’ (prostitutes, homosexuals), 2% criminals, and 1% Jehovah’s Witnesses. From 1943 the demand for labour soared, and the companies which benefited from the slaves of Ravensbrück were asked by the SS to provide some women to guard the prisoners. The majority of the labour prisoners were employed by Siemens or Halske, but Ruhrchemie, the firm I was working for, also utilised some prisoners.

In our only training, we attended a lecture vaguely explaining what tasks would be required of us, and were put to work straight after. Most of the other female guards were like me: young, single, with a little schooling, and from the surrounding region. A lot of them enrolled in the SS army for banal reasons, such as escaping their parents’ house, making more money than they could as simple maids or waitresses, or even to find a husband. Every morning, at about 6 a.m., we led a small group of prisoners away to do camp labour, such as building roads, sewing uniforms and shoes, growing fruits… We would come back every day for lunch, and would wait for new orders or possibly go away with the same squad in the afternoon. I was eventually supervising a crew making Nazi submarines and aircrafts for Siemens.

Ravensbrück was where SS females were trained before being sent to serve in death camps like Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen; among these women was the famed war criminal Irma Grese. My friend and I feared these experienced and harsh guards. Some of them were violent, brutal, and even bestial. They forced women prisoners to stand barefoot in the cold for hours; they beat and whipped them and ordered their German Shepherd dogs to mutilate them. Any slave who slowed production risked being struck. I remember that I cried once, when I saw a screaming child being carried away from his mother. I wasn’t expecting such ghoulish things to be happening there. When I started to work, I was very sensitive and maudlin about it, but step by step it became a simple routine. In time, us guards all turned our feelings off.

In spite of the fact that both my brothers served in Hitler’s army, my family didn’t have anything to do with the Nazis. I came from a social-democratic household. My parents were not opposed to the Nazis, but neither were they preaching their ideas. When Hitler was elected, I was only nine years old, and like any other German child, I didn’t escape the influence his power had on society. I read some anti-Semitic books and papers, and wanted to join the League of German Girls, but my father refused to let me. He was actually a mineworker with left-wing inclinations. When I visited him in autumn 1944 while escorting some prisoners back to the Ruhr, my hometown, he was furious to find out that I was working in this environment. Nonetheless, he advised me to obey the orders given to me, as he wanted me to stay out of trouble.

In 1945, due to the approaching Red Army, a gas chamber was built at Ravensbrück, and in February senior guards began to select, as silently as possible, people to be sent to death. I started to understand what was really going on when the main gate opened and I got a glimpse of the blood-stained pavement. Later, from the chalet where we lived, we saw some flames rising in shapes from the chimney of the crematorium. It was a nauseating and disgusting smell; it couldn’t have come from burning paper. My friend and I understood that people were being burnt there. A few months later, we were given the order to evacuate. All the guards got drunk with drinks the SS emptied from nearby German stores. We were asked to discard all SS documents and had to flee. Once before, I’d had the opportunity to leave the camp — I was suffering from thrombosis and wasn’t able to walk and stand without being in awful pain. I was judged unfit to work, and was ordered to resign. Yet the bond I had with my friends in Ravensbrück, as well as the fear of being on my own, not knowing where to go, made me refuse.

It was only a few years later, after having left the camp, that I realised I had taken part in inhuman actions. I feel guilty for the wartime role I played as a guard, even though I was a simple draftee, and was manipulated and lied to about the position of Ruhrchemie. I feel like I was made innocently guilty. I didn’t do anything wrong; I never struck anyone, and never even entered the prisoners’ enclosure. I wasn’t one of the criminal blonde beasts that female SS are usually depicted as. I did my best to be kind to prisoners and to make their life a little easier. We even spent some happy moments together; I still remember the afternoon we roasted potatoes in the field. They felt as much sympathy for me as I felt for them.

I didn’t have the choice to do what I was doing — our only goal as guards was to avoid any kind of trouble. We couldn’t simply step out of line. We stayed in the camp out of opportunism only. We were young and had the vivid desire to live. We feared the orders of the Kommandant, who told us that if we cried too often, we would become prisoners ourselves. This threat was omnipresent; we could feel the pressure weighing on us all the time. As simple guards, we didn’t know the worst things happening in the camps. In 1960, historians began to publish books on the topic, and after reading a book on the Holocaust, I realised how horrific these things were — too horrific to be put into words. Nevertheless, I feel guilty for the fact that I was standing there and watching, and had to close my eyes to the one thousand women dying each month. I wish to have my ashes spread in the camp as an apology to the prisoners whose ashes were spread in the lake. I have the feeling I belong there also.

The dreadful and paradoxical truth is that it was the most beautiful time of my life: I was young, free, and in love. The surroundings were beautiful, the landscapes breathtaking. Once off duty, we were allowed by the SS to have some freedom. Us female guards were allowed to invite men in the evening, and we were all flirting with SS officers or Siemens engineers. The horror at work was completely juxtaposed with the joy in our free time. I still remember the movie nights, the Wurst in town, and above all, the time I spent with my Prussian lover.